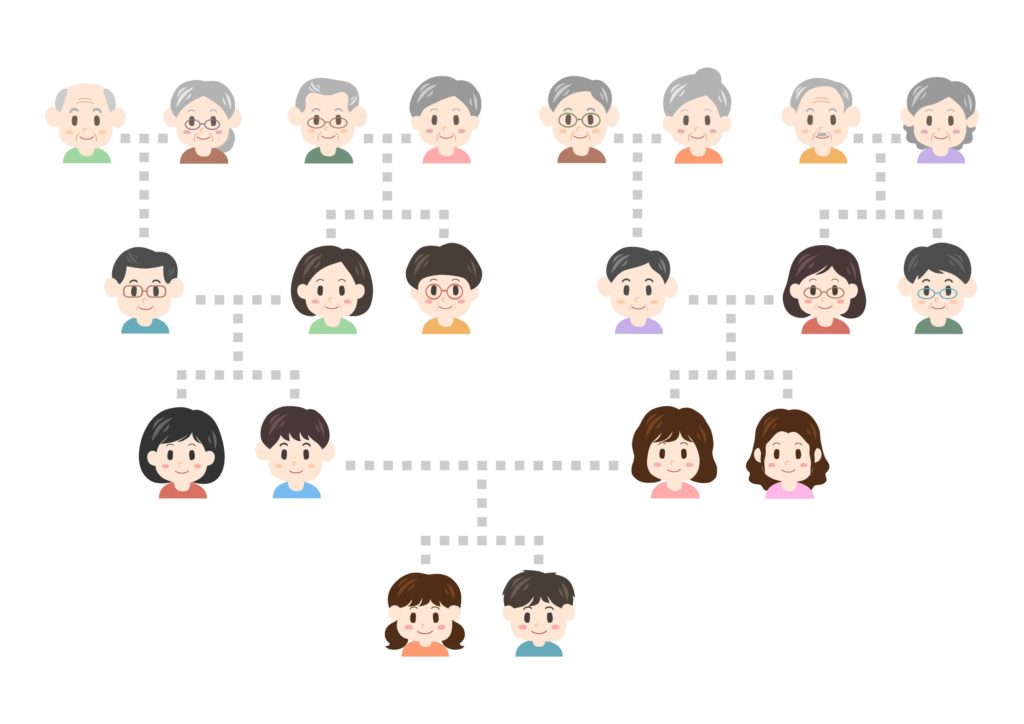

We inherit our cells’ mitochondria from our mother. These energy-producing organelles are present in large numbers in most cells, meaning that cells can contain thousands of copies of the DNA associated with the mitochondria (mtDNA)—all passed on wholly from our mother. New evidence suggests, however, that this cannon principle of maternal-only inheritance of mtDNA might need to be refined. And it all started with a four-year-old boy.

mitochondrial DNA

Harnessing the Power of Massively Parallel Sequencing in Forensic Analysis

The rapid advancement of next-generation sequencing technology, also known as massively parallel sequencing (MPS), has revolutionized many areas of applied research. One such area, the analysis of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) in forensic applications, has traditionally used another method—Sanger sequencing followed by capillary electrophoresis (CE).

Although MPS can provide a wealth of information, its initial adoption in forensic workflows continues to be slow. However, the barriers to adoption of the technology have been lowered in recent years, as exemplified by the number of abstracts discussing the use of MPS presented at the 29th International Symposium for Human Identification (ISHI 29), held in September 2018. Compared to Sanger sequencing, MPS can provide more data on minute variations in the human genome, particularly for the analysis of mtDNA and single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). It is especially powerful for analyzing mixture samples or those where the DNA is highly degraded, such as in human remains.

Continue reading “Harnessing the Power of Massively Parallel Sequencing in Forensic Analysis”Previewing ISHI 27: Mitochondrial DNA Analysis in Forensic Investigations

Heteroplasmy is the presence of more than one mitochondrial genome within an individual. Perhaps the most famous example of the effect of mtDNA heteroplasmy on a forensic investigation is the identification of the remains of Tsar Nicholas II. mtDNA from bones discovered in a mass grave in 1991, was identical in sequence to known relatives of the Tsar except at one position, where there was a mixture of matching (T) and mismatching (C) bases. Lingering doubt caused by this result meant that confirmation of the authenticity of the remains was delayed. Ultimately mtDNA analysis provided the needed evidence for identification, showing that the same heteroplasmy was present in mtDNA extracted from bones of the Tsar’s brother, confirming the Tsar’s identity (Ivanov et al., (1996) Nature Genetics 12(4), 417-20).

Here is what Dr. Holland had to say about the work he will present at ISHI:

Continue reading “Previewing ISHI 27: Mitochondrial DNA Analysis in Forensic Investigations”Mitochondrial DNA Typing in Forensics

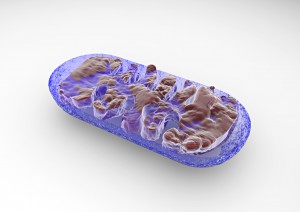

Mitochondria, often thought of as powerhouses of the cell, are fascinating eukaryotic organelles with a double-layered membrane and their own genome. Mitochondrial DNA (Mt DNA) is typically about 16570 bases, circular, highly compact, haploid and contains 37 genes, all of which are essential for normal mitochondrial function. Thirteen of these genes provide instructions for making enzymes involved in oxidative phosphorylation, a process that uses oxygen and simple sugars to create adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the cell’s main energy currency. The remaining genes code for transfer RNA (tRNA) and ribosomal RNA (rRNA) which are necessary for translating messenger RNA transcribed from nuclear DNA, into protein molecules.

Mitochondria, often thought of as powerhouses of the cell, are fascinating eukaryotic organelles with a double-layered membrane and their own genome. Mitochondrial DNA (Mt DNA) is typically about 16570 bases, circular, highly compact, haploid and contains 37 genes, all of which are essential for normal mitochondrial function. Thirteen of these genes provide instructions for making enzymes involved in oxidative phosphorylation, a process that uses oxygen and simple sugars to create adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the cell’s main energy currency. The remaining genes code for transfer RNA (tRNA) and ribosomal RNA (rRNA) which are necessary for translating messenger RNA transcribed from nuclear DNA, into protein molecules.

One of the most important characteristics of mitochondrial genome that is relevant to field of forensics is the copy number. Continue reading “Mitochondrial DNA Typing in Forensics”

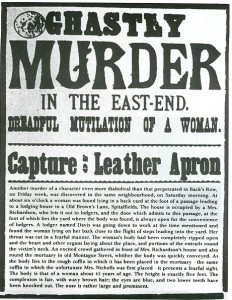

DNA Reveals the Identity of Jack the Ripper?

Image courtesy of the British Museum

In the late 1800s, Victorian England was mesmerized and horrified by a series of brutal killings in the crowded and impoverished Whitechapel district. The serial killer, who became known as “Jack the Ripper”, had murdered and mutilated at least five women, many of whom worked as prostitutes in the slums around London. None of these murders were ever solved, and Jack the Ripper was never identified, although investigators interviewed more than 2,000 people and named more than 100 suspects. Now, 126 years after the murders, a British author, who coincidentally has just published a book on the subject, is claiming that DNA analysis has revealed the identity of the notorious killer. DNA is often thought to be the “gold standard” of human identification techniques, so why is there so much skepticism surrounding this identification?

Continue reading “DNA Reveals the Identity of Jack the Ripper?”

From Where, the Dog’s Ancient Ancestor

We’ve learned this year, 2013, that Europe may be the original home to domestic dogs, a title previously claimed by East Asia and the Middle East. A recent study published in Science magazine may put to rest the debate.

In their report, Thalmann and Wayne (1) used an evidential gold standard, DNA from mitochondria of fossilized ancient dog and wolf remains, to reach the conclusion that dogs originated from a now extinct line of European gray wolves.

In 2002, researchers from Sweden and China collaborated to compared first the mitochondrial DNA and later the complete mitochondrial genomes and Y chromosomes from a hundreds of wolves, coyotes and modern dogs from around the world (2). Their results showed the greatest genetic diversity from canids from East Asia. Such genetic diversity can be a marker of a species’ origin.

In 2010 Wayne, et al. (3) analyzed 48,000 markers from across the genome of gray wolves and dogs, again from around the world. The dogs were found to have more genetic material in common with Middle Eastern wolves than with those from East Asia. Wayne and colleagues found this a yes to dogs’ origins lying in the Middle East.

A criticism of the analysis done with modern dog DNA is that this DNA has been mixed with that from wolves. In addition, dog-dog breeding over the 15,000 to 30,000 years since this domestication, could confound results. Prior to the current study, critics called for analysis of ancient DNA remains only.

Wayne had collected DNA from ancient remains and due to recent collaboration with geneticist Thalmann, now had the lab-power to analyze those remains.

In this work, Wayne and Thalmann looked at mitochondrial DNA from ancient remains, those of 18 wolves and dogs. The fossils ranging in age from 1,000 to 36,000 years. Eight of the samples were classified as dog-like and 10 samples were wolf-like in nature. They compared the ancient mitochondrial DNA samples to those of modern animals, including 77 dogs from an assortment of breeds, as well as 49 wolves and 4 coyotes. They then built a sort of a canid family tree, demonstrating relatedness in the animals whose DNA was analyzed.

Thalmann and Wayne’s finding showed that 1) the DNA of modern dogs more closely resembled that of ancient gray wolves than modern wolves, and 2) the geographic location of the wolves who’s DNA was most closely resembled, was Europe.

It is important to note that Thalmann and Wayne did not compare ancient remains from animals from the Middle East, nor did they have access to ancient remains from East Asia. In addition, there is criticism of the use of mitochondrial DNA, which represents only the maternal dog lineage. Thus there is more work to be done to finalize the ancestral home of the modern dog.

This work does, however, push back the origins of domesticated dogs to between 18,000 and 32,000 years ago, significant because the domestication timeline was previously believed to coincide with the rise of farming by our human ancestors. Domestic canines are now believed to have been part of humans lives far before farming was a way of life, back in the hunter-gatherer days.

There are those who believe that domestication of wolves, selectively bred to become modern dogs occurred simultaneously at more than one geographic region. Wolves were once found in many locations around the world and their usefulness to and domestication by humans would seem odd if only embraced by people from a single part of the world.

King Richard III Identified

By now, you’ve seen the headlines. The bones that scientists found buried under a car park in Leicester, England, have been identified as those of the last Plantagenet king of England: Richard III. For those of you who might be new to this story, archaeologists identified and excavated the most likely burial spot for Richard III, under a car park near the Leicester City Council building, and unearthed a human skeleton with skeletal abnormalities similar to those of Richard III. Geneticists were called in to perform DNA analysis to determine if these bones were those of the English king. The DNA findings were just recently released. Now that scientists can say beyond a reasonable doubt that these bones belong to Richard III, we are learning new things about the ancient king. Continue reading “King Richard III Identified”

By now, you’ve seen the headlines. The bones that scientists found buried under a car park in Leicester, England, have been identified as those of the last Plantagenet king of England: Richard III. For those of you who might be new to this story, archaeologists identified and excavated the most likely burial spot for Richard III, under a car park near the Leicester City Council building, and unearthed a human skeleton with skeletal abnormalities similar to those of Richard III. Geneticists were called in to perform DNA analysis to determine if these bones were those of the English king. The DNA findings were just recently released. Now that scientists can say beyond a reasonable doubt that these bones belong to Richard III, we are learning new things about the ancient king. Continue reading “King Richard III Identified”

Are These the Bones of Richard III?

In central England, an archaeological dig is happening in an unlikely spot—a parking lot in the city of Leicester. The goal: To find the final resting spot of Richard III, the last of England’s Plantagenet kings and perhaps one of its most maligned rulers. Richard III reigned over England for only two years before being killed by Henry Tudor’s army during the Battle of Bosworth Field in August 1485 at the end of the War of the Roses, which pitted Richard’s House of York against the House of Lancaster. Many historical records suggest that Richard’s body was brought to Leicester and buried between the nave and altar at Grey Friars church. You would think that a king’s tomb would be well marked and well remembered, even for an unpopular king like Richard III, but that is not the case here. Henry was said to have erected a memorial for his former rival, but that and any other monuments, along with the church itself, are long gone, destroyed during the Dissolution of the Monasteries, when Henry VIII was named Supreme Head of the Church in England and systematically razed monasteries, convents and friaries throughout England, Wales and Ireland between 1536 and 1541. Since then, the exact location of Richard III’s remains was lost to history. However, thanks to a team of University of Leicester archaeologists and geneticists that might be changing.

DNA Typing Confirms Bronze Age Mix-and-Match Burials

Archaeologists have made an interesting discovery while excavating the late Bronze Age/early Iron Age settlement named Cladh Hallan on the island of South Uist in the Outer Hebrides, Scotland. They have uncovered four human skeletons buried at regular intervals beneath three roundhouses dating from the 11th century BC: an adult male, an adult female, a 10–14-year-old girl and a 3-year-old child. The careful arrangement of these burials directly below the roundhouses led archaeologists to initially hypothesize that these might be foundation burials—an ancient practice in which people, usually younger people, were sacrificed and buried under a building’s foundation in the belief that their blood and spirit would protect and strengthen the building and building site. As strange as that custom seems to us, it gets weirder. Two of these skeletons showed signs of mummification and contained skeletal elements from multiple individuals intentionally pieced together to form intact skeletons. Continue reading “DNA Typing Confirms Bronze Age Mix-and-Match Burials”

Archaeologists have made an interesting discovery while excavating the late Bronze Age/early Iron Age settlement named Cladh Hallan on the island of South Uist in the Outer Hebrides, Scotland. They have uncovered four human skeletons buried at regular intervals beneath three roundhouses dating from the 11th century BC: an adult male, an adult female, a 10–14-year-old girl and a 3-year-old child. The careful arrangement of these burials directly below the roundhouses led archaeologists to initially hypothesize that these might be foundation burials—an ancient practice in which people, usually younger people, were sacrificed and buried under a building’s foundation in the belief that their blood and spirit would protect and strengthen the building and building site. As strange as that custom seems to us, it gets weirder. Two of these skeletons showed signs of mummification and contained skeletal elements from multiple individuals intentionally pieced together to form intact skeletons. Continue reading “DNA Typing Confirms Bronze Age Mix-and-Match Burials”

Was Dr. Crippen Innocent After All? New Forensic Evidence 100 Years After his Execution

The past few decades have seen amazing advances in forensic science that are instrumental in analyzing DNA evidence to put perpetrators of crimes behind bars and exonerate people convicted of crimes that they did not commit. [Read William Dillon’s story of wrongful conviction].

Unfortunately for some people, these techniques were developed too late. One of those people was Dr. Hawley Harvey Crippen, who was accused and convicted of killing his wife Cora in 1910 using the forensic techniques available at the time. Until the very day of his execution, Dr. Crippen insisted that he was innocent, and now there is strong DNA evidence to support his claim. Recently, forensic scientists from Michigan State University analyzed DNA evidence in this case and published their results in the Journal of Forensic Science (1): The human remains that were so instrumental in Dr. Crippen’s conviction were not those of his wife.