Globally, there have been over 5 million deaths attributed to COVID-19 since the start of the pandemic. Throughout the ongoing battle against SARS-CoV-2, researchers have been studying the viral lineage and the variants that are emerging as the virus evolves over time. The more opportunities that the virus has to replicate (i.e., the more people it infects), the greater the likelihood that a new variant will emerge.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) classify SARS-CoV-2 variants into four groups: Variants Being Monitored (VBM), Variants of Interest (VOI), Variants of Concern (VOC) and Variants of High Consequence (VOHC). So far, no variants in the US have been identified as VOHC or VOI. Currently, the most common variant in the US is the Delta variant (which includes the B.1.617.2 and AY viral lineages), and it is classified as a VOC.

The Delta variant originated in India and spread rapidly across the UK before making its way into the US (1). Current vaccines, including mRNA and adenoviral vector vaccines, have demonstrated effectiveness against the Delta variant. However, it is a VOC because it is more than twice as contagious as previous variants, and some studies have shown that it is associated with more severe symptoms.

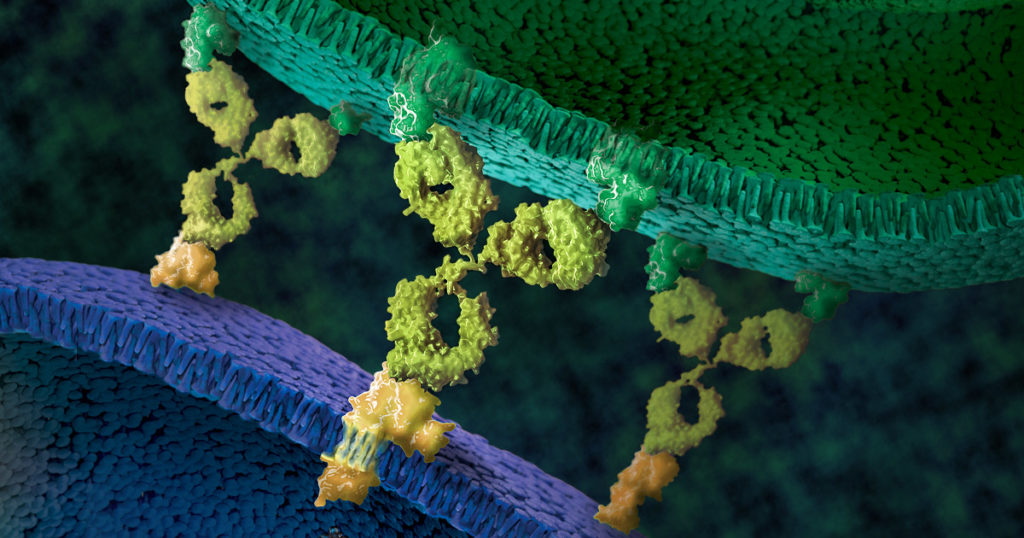

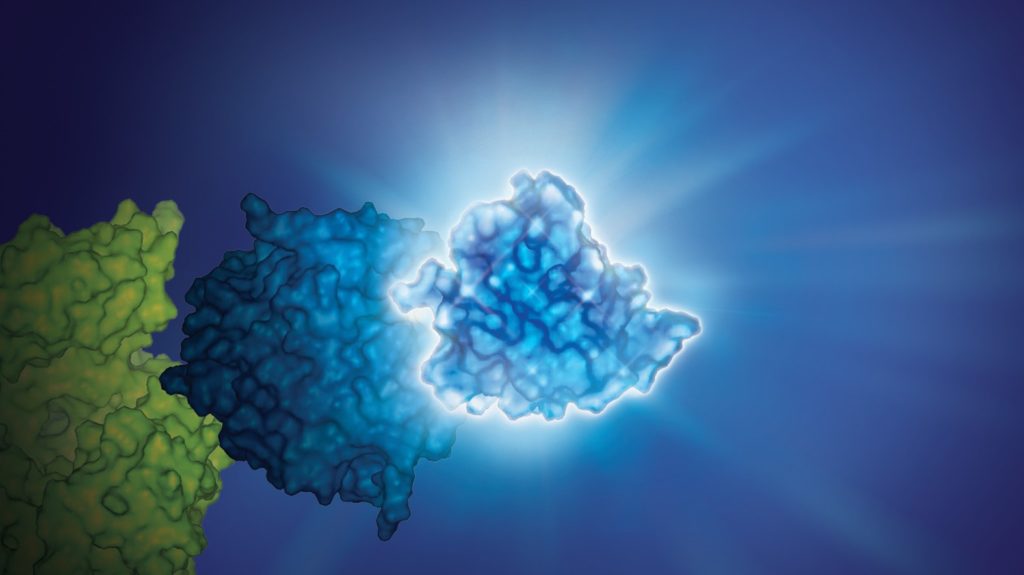

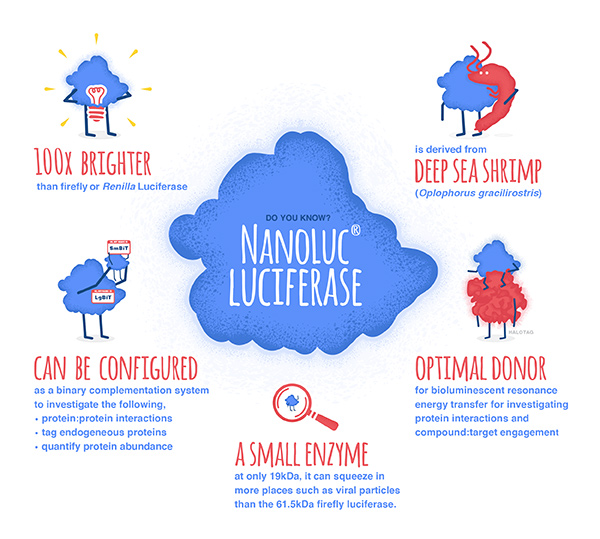

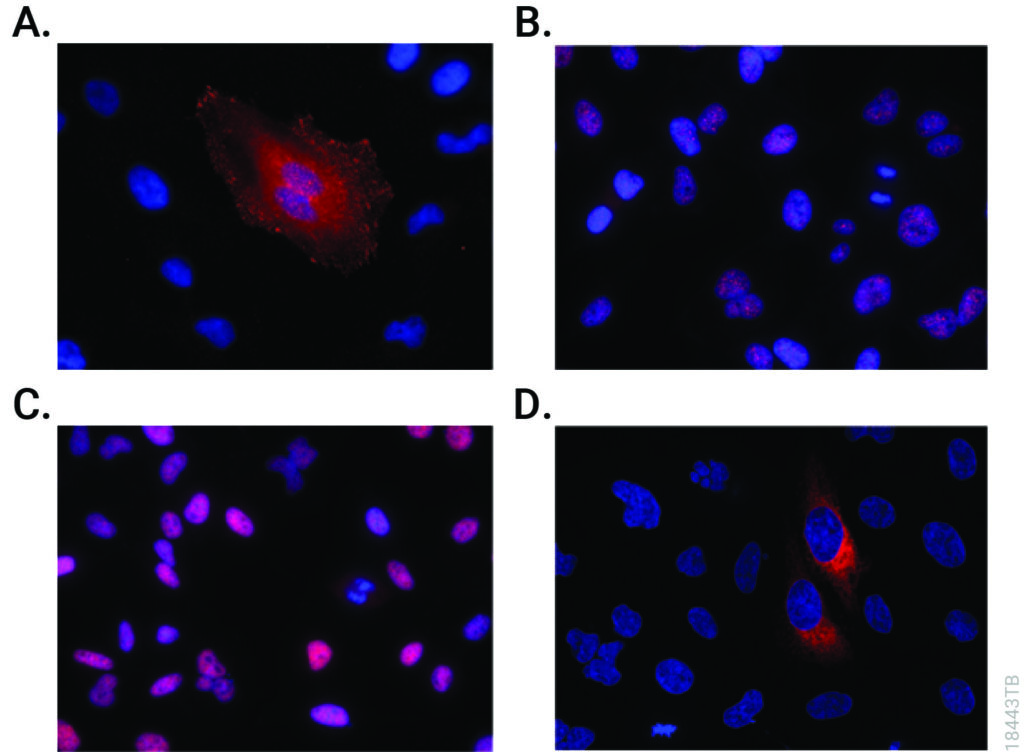

A recent study (2) provides one explanation for the higher infectivity of the Delta variant, using an approach based on virus-like particles (VLPs). The research team was led by Dr. Jennifer Doudna, 2020 Nobel Prize winner for her work on CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing, and Dr. Melanie Ott, director of the Gladstone Institute of Virology at the University of California–Berkeley.

Continue reading “Virus-Like Particles: All the Bark, None of the Bite”