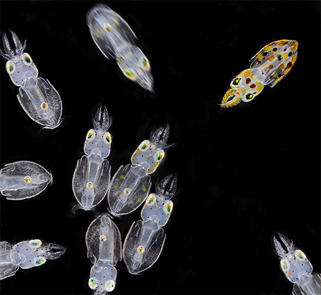

Squids are mysterious creatures roaming seas and oceans. They are also the subjects Urs Albrecht chose for his winning picture in the Swiss Art + Science competition, “One Out.” The photo shows squid juveniles, one of which displays striking colors in opposition to the rest. The bright individual is also physically removed from the group, may be scared or angry. The image is fascinating because we can see complex biology at play with the naked eye. Squids are Coleoid cephalopods, mollusks with arms attached to their heads. They have lost their shell and developed larger and highly differentiated brains and camera-type eyes through evolution. Their nervous system is highly organized. The central brain acts as the decision-making unit, and the peripheral nervous system processes motor and sensory information.

Like all Coleoid cephalopods, squids show an impressive repertoire of body patterns for camouflage, social communication, and signaling. They can change their appearance to match their surroundings or stand out. This is made possible by the specialized cells and tissues in squids’ skin. In the upper layers, chromatophores are cells containing red, yellow, or brown pigments. They are attached to muscles directly innervated by the brain. The muscles’ contraction and relaxation increase or decrease the surface of chromatophores’ pigmented sacs, enabling cephalopods to produce various patterns, such as bands, stripes, and spots. In deeper skin layers, iridophores are colorless cells. Structural elements within iridophores reflect specific wavelengths of light back out and change color depending on the angle of view, making the skin iridescent. Despite being color-blind, squids exert exquisite control over the appearance of their skin, and they can change how they look in the blink of an eye (50-200 ms). Not much is known about the mechanism underlying the control. A theory is that squids can detect light through their skin, maybe thanks to opsins like cuttlefish. The change in appearance is probably primarily reflexive, but it can also be voluntary, as the squids’ behavior and intelligence attest.

“Humans must be humbler towards nature when looking at it because although we always say we are better, we are not. We are very similar and not much different.”

Urhs Albrecht

Squids camouflage to hunt or evade predators. Some have adapted the original concealing function to communicate with each other. Finding a mate and eliminating competition in the vast ocean is not easy. Male Caribbean reef squids use a binary code: red to attract females and white to deter males. But sometimes, they need to send more than one message at once. They then split the coloration of their bodies to attract a female on one side and repel a male on the other! The Humboldt Squid, also called “Jumbo Squid,” communicates through red to white color flashes with its conspecifics. It can modulate their frequency and amplitude or even synchronize them with others. The Humboldt Squid also produces its own light thanks to photophores containing the luciferase enzyme and its substrate, the luciferin. Firefly squids, found on Japanese shores, are also intrinsically bioluminescent, while the bobtail squid borrows the ability to glow from the bacteria it homes in its light organ. Camouflage and flashes are not the only defensive tools Coleoid cephalopods have in their arsenal. Those that dwell on the brighter surfaces have an ink sac. When threatened, they can expel a dark cloud to confuse attackers and flee. Their deep-sea cousins, like the vampire squid, squirt a sticky bioluminescent mucus instead.

Squids are a prime example of what Urs, the author of “One Out,” said: “Humans must be humbler towards nature when looking at it because although we always say we are better, we are not. We are very similar and not much different.” Indeed, like us, squids see, feel, and communicate. Because we do not understand them, and scientists have yet to decipher their language, does not mean we should dismiss squids.

General References

- Meyer, F. (2013) How Octopuses and Squids Change Color Smithsonian [Internet: Accessed 5/18/2002]

- Mather, J. (2013) The Imitation Game The Biologist 65(6): 10–13. [Internet: Accessed 5/18/2022]

- Duruz, et al. (2022) Molecular Characterization of Cell Types in the Squid Loligo vulgaris bioRxiv preprint server [Internet: Accessed 5/18/2022]

- Amodio, P. et al. (2019) Grow Smart and Die Young: Why Did Cephalopods Evolve Intelligence? Trends in Ecology and Evolution 31(1): 45–56. [Internet: Accessed 5/18/2022]

- Mäthger, L.M. et al. (2008) Mechanisms and behavioural functions of structural coloration in cephalopods. Journal of the Royal Soceity Interface [Internet: Accessed 5/18/2022]

- Gilmore, B.S. et al. (2016) Cephalopod Camouflage: Cells and Organs of the Skin. Scitable [Internet: Accessed 5/18/2022]

- Wikipedia Firefly Squid [Internet: Accessed 5/18/2022]

- Burford, B.P. and Robison, B.H. (2020) Bioluminescent backlighting illuminates the complex visiual signals of a social squid in the deep sea. PNAS 117(15): 8524–31.

- Carnall, M. (2017) Why do cephalopods produce ink? And what’s ink made of anyway? The Guardian [Internet: Accessed 5/18/22]

- Pearson, H. ( 2001) Blame it on the bugs. Nature [Internet: Accessed 5/18/2022]