Microbiome research is booming right now, with more and more evidence that our personal health and environment are shaped and influenced by the microbes we harbor and encounter. One area of study I find particularly interesting is how the microbiome we acquire at birth affects our long-term health.

A flood of new findings have emerged related to infant microbiome research, leaving parents like me scratching their heads about whether the secrets to our children’s future health may exist in the seemingly endless stream of dirty diapers we change.

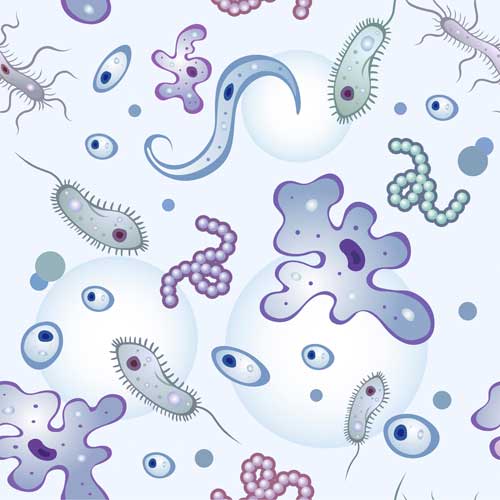

The human microbiome evolves and develops in utero and then during and after delivery is colonized by bacteria encountered during exposure to the external environment. The initial composition of microbes an infant is populated with influences their lifelong microbiome signature and can be influenced by many factors along the way, including the microbiome community of the mother, use of antibiotics or other antibacterial substances, breastfeeding, C-section birth. These variables have been correlated with disruption of the infant microbiome and associated with differences in cognitive development and the development of disease, such as asthma and allergies.

In general, these correlations are discovered by taking a fecal sample from an infant and analyzing the DNA sequences of the bacteria present. The microbiome composition of the individual is then compared against different individual characteristics (such as presence or absence of a disease) at the time of the sample and/or at later points in time. Finally researchers look for statistically significant patterns among individuals with similar characteristics or microbiome communities. This type of study can reveal associations between the microbiome and individual traits, but further experiments are needed to show causation.

Continue reading “Predicting the Future with Dirty Diapers”