This post is written by guest blogger, Peter Kritsch MS, Adjunct Instructor BTC Institute.

When I was in the middle of my junior year in high school, my family moved. We had lived in the first state for 12 years. I had gone to school there since kindergarten. Although it wasn’t a small district, I knew everybody and, for better or worse, everybody knew me. Often the first reaction I get when I tell people when we moved is that it must have been hard to move so close to graduation. The reality is . . . it really wasn’t. In fact, it was quite liberating. See, I didn’t have to live up to anybody else’s expectations of who I was based on some shared experience in 2nd grade. I had the opportunity to be who I wanted to be, to try new things without feeling like I couldn’t because that wasn’t who I was supposed to be.

As long as I refrained from beginning too many sentences with “Well at my old school . . . “ people had to accept me for who I was in that moment, not for who they perceived me to be for the previous 12 years. Now, the new activities were not radically different. I still played baseball and still geeked out taking AP science classes, but I picked up new activities like golf, playing basketball with my friends, and even joined the yearbook. I know . . . “radically different.” The point is that the new situation allowed me to try something new without worrying about what had always been.

The pandemic has forced a lot of us to move our classrooms online. In a short period of time, everything changed about how education was done. Our prior teaching experience, including the experience I had with doing blended learning (ooops . . . “back at my old school”), was helpful to a point. But we quickly found out that being completely virtual was different. And as science teachers, how do you do more than just teach concepts when online? How do you help students to continue engaging in the crucial parts of science – observing, questioning, designing, analyzing, and communicating?

In my pre-pandemic biotechnology class, an important part of the class was the lab notebook. These were Composition-style notebooks where students wrote introductions, made predictions, pasted directions, made observations, and analyzed their results. You know, the typical lab report. The lab entries often covered more than 5 pages and, if done correctly, were really works of art. Their detailed writing allowed students to process what they learned. But how well does the lab book format work when we are online with students who are being asked to simulate a lab experience?

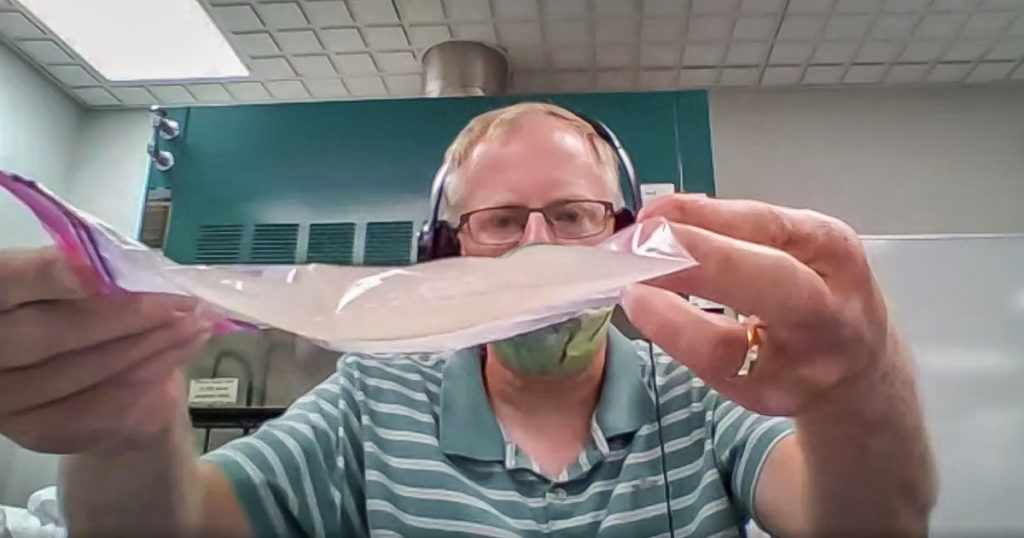

What I decided to do was to give myself permission to do something different. After 19 years of using lab books, I decided to give recorded oral reports a try. Students were given the basic outline of what I wanted covered for each lab report – basic background information, an overview of the lab directions, a labeled picture of the results, an analysis of those results, and a summary of what they had learned. Students were encouraged to create their own slides to share during their presentation and given a target duration of 5 minutes. Students made their videos using Flipgrid – there are a lot of different resources available for screen recording.

What did I find? I was really surprised. There were so many positives. For one, I didn’t have 40 lab books to take home with 200 or more pages to grade over a weekend. The literal and figurative weight of that proposition was gone. Second, students could be more creative. The lab book directions were very proscriptive – write this here, paste that here, label this picture and you will score well. The oral reports were more open ended, but I heard the students’ lab experiences in their own words. I saw numerous ways to represent how gel electrophoresis works and a wonderful demonstration of how to use a micropipette.

I feel like I got to know my students better. I don’t think I have smiled as much in 2 months of grading these oral reports as I did in 19 years of grading lab books. My students are great kids. While I knew that before the pandemic, I am reminded of it with almost every oral lab report. Finally, I still saw the elements of a good scientific report just in different ways. Students still had to relay their observations, analyze their results, and suggest new experiments based on those results.

Now, not all is sun and roses. The oral lab reports do not have nearly the amount of detail as the written lab report. They can’t. They are only 5 minutes long. But, students are still practicing their communication skills and, most importantly, they are demonstrating what they have learned.

Will I go back to written lab books when I finally get back to the classroom? Maybe. I may somehow blend the two together with a short video report and an open-lab book lab test. It’s a question I look forward to wrestling with as it would mean that we are back in the classroom. But by giving myself permission to try something new, to be someone different, I feel that I grew as a teacher and learned more about what works for my students.

Explore more resources for online science teaching at the BTC Institute website.

Peter Kritsch received his B.S. in Biology from Valparaiso University and his M.S. in Cell and Molecular Biology from UW-Madison. He has a teaching certification in Biology and has taught Biology and Biotechnology to high school students for 14 years at Oregon High School in Oregon, Wisconsin. He has also served as advisor to approximately 50 OHS students in the Biotechnology Youth Apprenticeship Program.