As the SARS-CoV-2 virus spread around the world in early 2020, many researchers shifted their focus to support the global endeavors to address the challenge. For two professors at the University of Wisconsin, their efforts started with animal models to study pathogenicity and grew into massive SARS-CoV-2 sequencing and COVID-19 testing projects.

“Being a scientist in this field gives a sense of purpose, but also a sense of obligation and responsibility,” says David O’Connor, PhD. “You always want to feel like you’re living up to that.”

Shifting Focus to COVID-19

David and spouse Shelby O’Connor, PhD, both lead labs at the Wisconsin National Primate Research Center at the University of Wisconsin – Madison.

David and Shelby are part of a longtime collaborative group that works together on animal models of infectious diseases such as HIV and tuberculosis. Over the years, the team has shifted focus at times to address emerging threats. For example, when the Zika virus escalated to an epidemic in 2015, they supported global research efforts by developing a model to study Zika virus during pregnancy using a primate model.

At the beginning of 2020, David was in South Africa when news of the novel coronavirus emerged from China. He called Shelby to start discussing how their group of labs could pitch in to the response.

“January 22nd was the day we started thinking about this,” David says, “and within a couple of weeks I would say it was taking up 50% or more of our mental bandwidth.”

They started working with the animal models with which they were most familiar, developing systems in nonhuman primate models to study the pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2. This work kept them busy until the beginning of March, when Madison, WI began experiencing community spread of COVID-19. By that point, David says, it was nearly a 24-hour job.

“Some nights, [UW Professor and collaborator] Tom Friedrich, Shelby, or I would be in the lab until two in the morning. It was a race against time to figure out what was going on, and from then on it’s been an all-out effort.”

Over the next few months, the O’Connor’s expanded their focus beyond just animal models. As virologists, they realized they had the skills and knowledge to make a positive impact on their community. David says he was inspired by a visit to the world-class Rakai Health Sciences Program, one of the leading institutions for HIV research. He noticed how everyone pitched in when a job needed to be done.

“You could be the clinical medical director, but if the car didn’t start, you had to change the battery,” David says. “Everybody had to play their part, whatever that was. So when there was a virus in our own community…we looked at the important things that needed to be done and said, ‘We can do that.’”

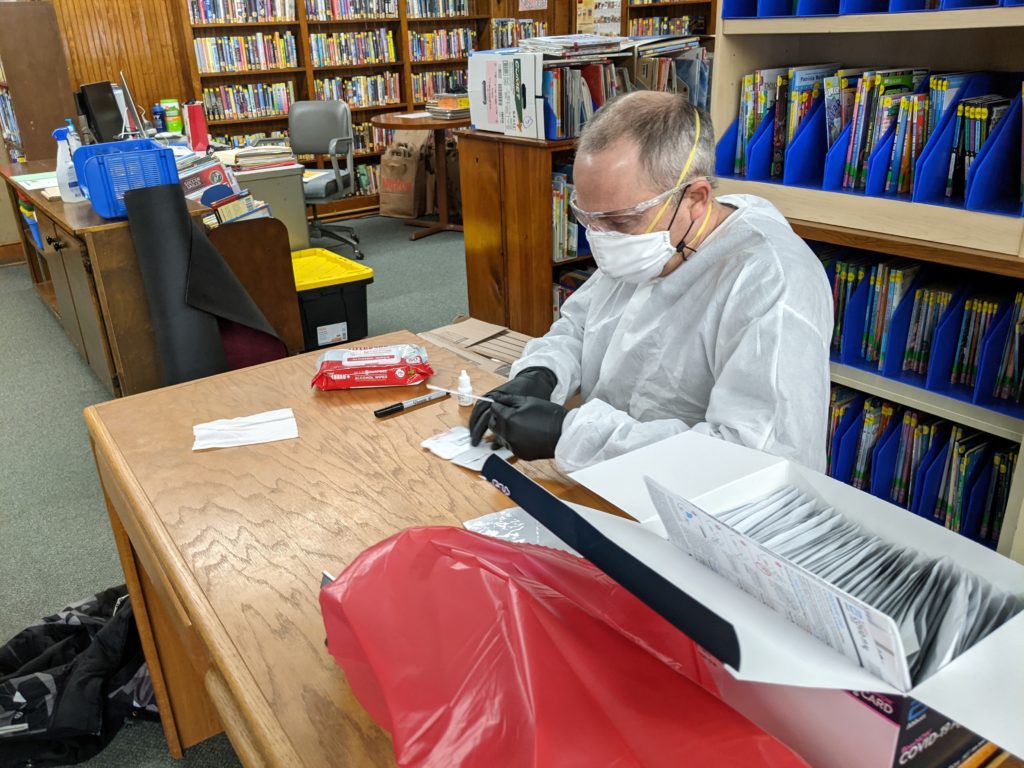

Today, David’s team has sequenced over 3,500 viral samples. David and Shelby have also been working together to facilitate COVID-19 testing at K-12 schools in the greater Madison area. In many ways, COVID-19 has become a full-time job for the O’Connor’s, but both say they’re excited to be pushing ahead.

“You have to listen to the experts,” Shelby says, “but we recognize that you don’t have to be an expert in everything to make a difference.”

SARS-CoV-2 Sequencing

One of David’s biggest projects over the past year has been tracking how SARS-CoV-2 moved and changed in both time and space. Working with Tom Friedrich’s lab, David’s team has been sequencing SARS-CoV-2 viral genomes extracted from positive test samples in Dane County, WI.

The genome of SARS-CoV-2 consists of approximately 29,900 bases of RNA. Those bases contain the instructions for assembling each piece of the virus – the spike protein, which gives the virus access to host cells, along with 28 other known proteins.

When a virus replicates, there is a small chance that any number of those bases will be copied incorrectly. Every mutation that is introduced could result in a change in phenotype. These changes could lead to a biological effect such as the increased transmissibility of the B.1.1.7 variant of SARS-CoV-2 that emerged in the United Kingdom, or the reduced susceptibility to certain vaccines of the B.1.351 variant in South Africa.

However, even mutations with no noticeable consequences to human health can be useful for understanding the pandemic.

“Sequencing provides a fingerprint that allows you to follow the virus through time and space,” David says. “You can figure out how the sequences in Milwaukee and the sequences in Madison compare to each other before and after a ‘Safer At Home’ order, for example. And we did this last year. It turns out that during ‘Safer At Home,’ the Madison viruses stayed in Madison and the Milwaukee viruses stayed in Milwaukee. After the Wisconsin Supreme Court struck it down, you saw more mixing of the viruses.”

The team uses a Maxwell® RSC 48 instrument to extract viral RNA with the Maxwell® RSC Viral Total Nucleic Acid Purification Kit to prepare their samples, which are then sequenced on an Oxford Nanopore platform. They’re currently able to process around 200 samples per week. Since the beginning of the pandemic, they’ve sequenced approximately 5% of all positive test samples in Dane County. This is a huge increase from the national average, which is below 0.5%.

“People would say, ‘Are you doing this for research or for public health?’ And it was like, yes!” David says. “We want to learn about the virus, but the act of generating the sequence has public health value at the same time.”

David and his team work with other researchers and officials to compare sequencing data and monitor how the virus changes in Wisconsin. Together, they’ve been tracking the viral variants throughout Wisconsin and watching closely for concerning variants such as B.1.1.7. David was one of the first to be notified when a case of B.1.1.7 was discovered in Waukesha County in early February.

“We couldn’t do any of this without the public health input and without our testing lab partners,” David says. “It really is a huge community effort.”

That community effort will hopefully grow in the coming months as the United States allocates more resources to viral sequencing. On February 4, 2020, Wisconsin Senator Tammy Baldwin introduced legislation to provide CDC with $2 billion with the goal of sequencing SARS-CoV-2 genomes from 15% of COVID-19 infections in the United States.

“We’re going full steam ahead with the expectation that there’s going to be an ongoing need for viral sequencing,” David says.

COVID-19 and Open Science

All of the sequencing data generated by the O’Connor and Friedrich labs are available in an open-access portal. The portal also contains extensive protocols and data from four other COVID-19-related initiatives the team is working on, including animal models for pathogenesis. This practice of open science is something they’ve done for years, and they believe is valuable to the scientific community.

“We started sharing our data during Zika,” David says. “Shelby and I have been working in Brazil for a long time, so we were in a position to have some of the first data. We decided to open it up so that others who were just beginning to start planning would be able to benefit from our data. And so it became a logical extension that when we started working on COVID-19, we would basically follow the same template.”

David and Shelby both say they’re encouraged by the trend of publishing work in preprint servers such as medRxiv and bioRxiv. Both of them believe that science overall is trending to be more open. They also believe that sharing their data in near real-time has pushed them to do better work overall.

“Before we put something online, we have to be sure that we’re okay with anyone in the world seeing it. Sometimes that means we have to be pretty rigorous about what we say and do,” Shelby says.

Despite the challenges and unique experiences of the past year, David and Shelby say they’re inspired to continue supporting the research efforts and the safety of their community.

“It can be emotionally exhausting,” Shelby says. “There are some things that I never expected I’d be doing a year ago. I remember sitting outside one of the dorms in the van when it was raining, just waiting to get samples.”

“But it’s worth it,” she says, and David nods in agreement. “We’re moving ahead.”

Promega is proud to support researchers investigating SARS-CoV-2 and helping to overcome the COVID-19 pandemic. To learn more, visit our resources for viral research and vaccine development or check out the Corporate Responsibility Report for an overview of how Promega products have been used in crucial research.