When someone is admitted to a hospital for an illness, the hope is that medical care and treatment will help them them feel better. However, nosocomial infections—infections acquired in a health-care setting—are becoming more prevalent and are associated with an increased mortality rate worldwide. This is largely due to the misuse of antibiotics, allowing some bacteria to become resistant. Furthermore, when an antibiotic wipes out the “good” bacteria that comprise the human microbiome, it leaves a patient vulnerable to opportunistic infections that take advantage of disruptions to the gut microbiota.

When someone is admitted to a hospital for an illness, the hope is that medical care and treatment will help them them feel better. However, nosocomial infections—infections acquired in a health-care setting—are becoming more prevalent and are associated with an increased mortality rate worldwide. This is largely due to the misuse of antibiotics, allowing some bacteria to become resistant. Furthermore, when an antibiotic wipes out the “good” bacteria that comprise the human microbiome, it leaves a patient vulnerable to opportunistic infections that take advantage of disruptions to the gut microbiota.

One such bacteria, Clostridium difficile, is of growing concern world-wide since it is resistant to many different antibiotics. When a patient is treated with an antibiotic, C. difficile can thrive in the intestinal tract without other bacteria populating the gut. C. difficile infection is the leading cause of antibiotic-associated diarrhea. While symptoms can be mild, aggressive infection can lead to pseudomembranous colitis—a severe inflammation of the colon which can be life-threatening.

C. difficile causes disease by releasing two large toxins, TcdA and TcdB. Understanding the role these toxins play in colonic disease is important for treatment strategies. However, most published research data only report the effects of the toxins independently. A 2016 study demonstrated a method of comparing the toxins side-by-side using the same time points and cell assays to investigate the role each toxin plays in the cell death that leads to disease of the colon. Continue reading “A Tale of Two Toxins: the mechanisms of cell death in Clostridium difficile infections”

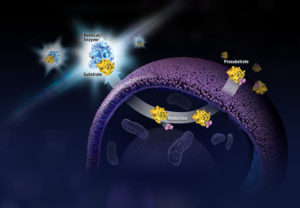

What if you could uncover a small but significant cellular response as your population of cells move toward apoptosis or necrosis? What if you could view the full picture of cellular changes rather than a single snapshot at one point? You can! There are real-time assays that can look at the kinetics of changes in cell viability, apoptosis, necrosis and cytotoxicity—all in a plate-based format. Seeking more information? Multiplex a real-time assay with endpoint analysis. From molecular profiling to complementary assays (e.g., an endpoint cell viability assay paired with a real-time apoptosis assay), you can discover more information hidden in the same cells during the same experiment.

What if you could uncover a small but significant cellular response as your population of cells move toward apoptosis or necrosis? What if you could view the full picture of cellular changes rather than a single snapshot at one point? You can! There are real-time assays that can look at the kinetics of changes in cell viability, apoptosis, necrosis and cytotoxicity—all in a plate-based format. Seeking more information? Multiplex a real-time assay with endpoint analysis. From molecular profiling to complementary assays (e.g., an endpoint cell viability assay paired with a real-time apoptosis assay), you can discover more information hidden in the same cells during the same experiment. Life is complicated. So is death. And when the cells in your multiwell plate die after compound treatment, it’s not enough to know that they died. You need to know how they died: apoptosis or necrosis? Or, have you really just reduced viability, rather than induced death? Is the cytotoxicity you see dose-dependent? If you look earlier during drug treatment of your cells, do you see markers of apoptosis? If you wait longer, do you observe necrosis? If you reduce the dosage of your test compound, is it still cytotoxic?

Life is complicated. So is death. And when the cells in your multiwell plate die after compound treatment, it’s not enough to know that they died. You need to know how they died: apoptosis or necrosis? Or, have you really just reduced viability, rather than induced death? Is the cytotoxicity you see dose-dependent? If you look earlier during drug treatment of your cells, do you see markers of apoptosis? If you wait longer, do you observe necrosis? If you reduce the dosage of your test compound, is it still cytotoxic?