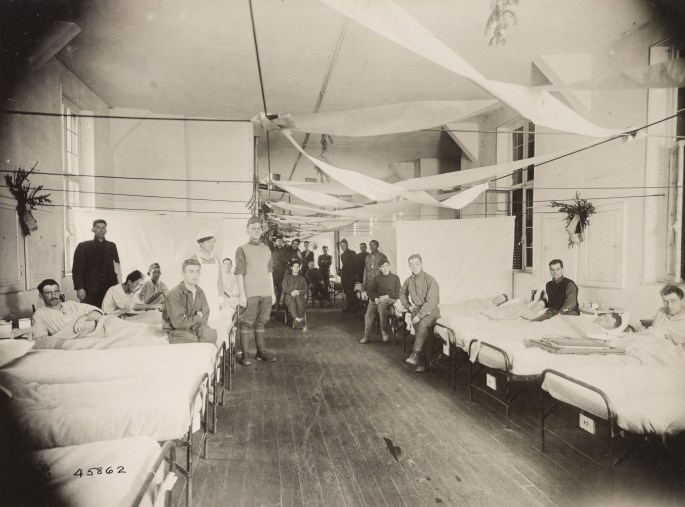

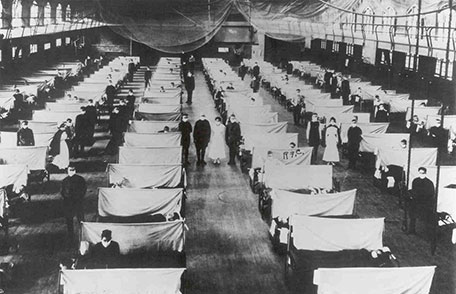

One hundred years ago, the world was taking its first deep breaths as it celebrated the end of World War I. The Armistice of Compiègne, was signed on November 11,1918, officially ending the four-year long conflict, which claimed the lives of more than 8 million soldiers (1). What the world didn’t yet realize was that they had been battling a far deadlier enemy in the hospitals and at home than any army the soldiers faced on the fields of war.

During the last year of the war, a deadly influenza virus rampaged around the globe leaving between 50 and 100 million dead in its wake.

The boys were coming in with colds and a headache and they were dead within two or three days. Great big handsome fellows, healthy men, just came in and died. There was no rejoicing in Lille the night of the Armistice.

Sister Catherine Macfie from her post at casualty clearing station no. 11 at St André near Lille, France (2).

A Deadly Pandemic

The world had seen influenza outbreaks before, but the variant that appeared in 1918 was different. It struck quickly, and killed ruthlessly. And it wasn’t just how fast or how many it killed that made this influenza unusual, it was also who it killed. Typically, it is the very old and the very young who are most vulnerable to influenza. In 1918, it was young and healthy adults ages 20–40 who accounted for over half the influenza-related deaths (3,4).

Roy Grist, a doctor at an army training base outside of Boston, MA, wrote to a colleague describing the influenza among the troops:

We have been averaging about 100 deaths per day…For several days there were no coffins and the bodies piled up something fierce… (5)

Camp Devens, where Dr. Grist was stationed, had over 14,000 cases of influenza by the end of September, resulting in 757 deaths (2). In Bohain, France, Captain Geoffrey Keynes of the Royal Army Medical Corps wrote:

There were rows of corpses, absolutely rows of them, hundreds of them, dying from something quite different. It was a ghastly sight, to see them lying there dead of something I didn’t have the treatment for (2).

While the young and strong were dying, the older generation (those over 65) were less likely to get sick. Those over 65 accounted for only 0.6% of the 1918 influenza cases, and those over 75 had a mortality rate lower than the prepandemic years of 1911–1916 (3).

The influenza pandemic of 1918 was the deadliest in modern history. In the United States alone, it claimed over 670,000 lives—a death toll higher than that for US soldiers lost in the war. In fact, the 1918 pandemic claimed more American lives than WWI, WWII, the Korean conflict and the Viet Nam War added together (6). World-wide, the death toll was over 50 million.

Searching for a Universal Vaccine

Seasonal influenza can be deadly. The World Health Organization estimates that 300,000 to 500,000 people die annually from influenza (WHO). The number of deaths vary depending upon the strain of influenza that is in circulation on a given year. While we haven’t experienced another pandemic like the one in 1918, most experts think it is only a matter of time before another devastatingly deadly strain emerges.

Seasonal influenza vaccines are made available every year, but even with advances in technology, these vaccines are only partially effective. These vaccines are expensive and time-consuming to produce (7). They are also likely to bring little or no protection from a new pandemic strain (8).

At the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, developing a universal influenza vaccine that would offer broader protection is a research priority (10). In 2017, they organized a workshop to bring experts together to identify areas where research needs to be focused. They also established parameters to target for a universal influenza vaccine: the vaccine would offer at least 75% protection against symptomatic disease from group 1 or 2 influenza A viruses, and would last at least 12 months in all populations (8).

Universal Vaccines: Targeting the Hemagglutinin or the Neuraminidase?

One of the biggest challenges for a universal influenza vaccine is the year-to-year changes that influenza viruses undergo. Most of these changes occur on one area of the viral molecule, the cap of the hemagglutinin. If you image the virus as a sphere covered with protein spikes, the hemagglutinin are these spikes. Each spike of hemagglutinin looks something like a mushroom, with a stalk and a cap. The hemagglutinin facilitates infection by binding to the cell-surface receptors of host cells, with the cap region changing between strains and between seasons through antigenic drift. Current influenza vaccines target the cap region; however, the stalk region is relatively conserved and might make a better target for a universal vaccine.

Targeting a vaccine, and thereby the body’s immune system, to the stalk of the hemagglutinin could result in broader protection from influenza. This approach has shown some promise. Tests with an mRNA vaccine targeting the hemagglutinin stalk showed that it elicited a strong antibody response in mice, protecting them from lethal doses of three influenza strains (10).

An mRNA vaccine uses mRNAs that encode hemagglutininproteins instead of the protein themselves. The mRNA molecules are injected into the host, where they are used by the host’s immune system to generate the protein. Because the host’s cells are producing viral proteins, it creates a much stronger antibody response. While still relatively new technology, mRNA vaccines offer an advantage over traditional protein-based vaccines because it is much easier to create mRNA that encode new hemagglutinin proteins than to create the proteins themselves.

If vaccines targeting the stalk region continue to be successful as they are developed further, they will undoubtedly offer broadened protection from influenza infection and move the needle closer to a universal vaccine. The stalk region can mutate in response to exposure to antibodies (11). While it takes more to induce changes to this region, it is possible that the stalk may not be conserved enough for a truly universal vaccine.

If the hemagglutinin is the mushroom-like spikes on the virus surface, the neuraminidase is the smooth surface in between. This surface glycoprotein plays an important role in viral replication. Studies in mice have shown that vaccination with neuraminidase-targeted antibodies show that this approach offers protection from several influenza subtypes (12). Targeting the neuraminidase might also have the added benefit of decreasing the severity of disease when it does occur. A controlled study in humans showed that the presence of preexisting neuraminidase antibodies performed better than antibodies toward the hemagglutinin at reducing disease severity, decreasing symptoms and shortening the duration of viral shedding. (10).

Conclusion

Even after a century, the horror of the 1918 influenza hasn’t faded from our memory. If a pandemic virus with the pathogenic properties of the 1918 virus appeared in the population today, we would be better able to defend ourselves, but no one is foolish enough to believe the results would not still be tragic and far-reaching. This possibility haunts scientists and public health officials, but even as funding and research continues to increase, the universal vaccine remains elusive.

References

- PBS: https://web.archive.org/web/20161016014336/http://www.pbs.org/greatwar/resources/casdeath_pop.html

- Wever et al. (2014) Death from 1918 pandemic influenza during the First World War: a perspective from personal and anecdotal evidence. Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses 8(5), 538–546.

- Center for Disease Control (CDC) website. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/12/1/05-0979_article

- Taunbenberger et al. 2006. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12 12-22.

- Barry, J. (2017) How the Horrific 1918 Flu Spread Across America. Smithsonian Magazine November 2017.

- McKinsey, D.S. et al. (2018) The 1918 influenza in Missouri, Centennial Remembrance of the Crisis Part 1. Missouri Medicine

- Mossad, S.B. (2018) Influenza Update 2018–2019: 100 Years after the Great Pandemic. Cleveland Clinical J of Medicine 85, 861.

- Paules, C. et al. (2017) The Pathway to Universal Influenza Vaccine. Immunity 47, 599.

- Pardi, N. et al. (2018) Nucleoside-modified mRNA immunization elicits influenza virus hemagglutinin stalk-specific antibodies. Nature Communications 9.

- Anderson, C. et al. (2017) Scientific Reports 7.

- WohlboldTJ, et al. (2015). Vaccination with adjuvanted recombinant neuraminidase induces broad heterologous, but not heterosubtypic, cross-protection against influenza virus infection in mice. mBio 6:e02556. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.02556-14.

- Job, E.R. (2018) J. Virol 92:e01584-17. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01584-17.

Kelly Grooms

Latest posts by Kelly Grooms (see all)

- Avoid the Summertime Blue-Greens— Know about Cyanobacteria Before You Hit the Water - July 8, 2025

- Growing Our Understanding of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer in Sub-Saharan Africa: Why Comprehensive Population Data Matters - June 5, 2025

- Measles and Immunosuppression—When Getting Well Means You Can Still Get Sick - April 17, 2025