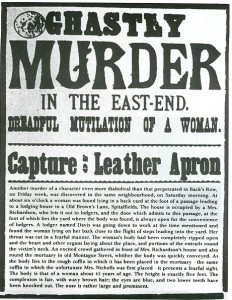

When DNA evidence is collected at a crime scene, submitting the sample for a search within a DNA database does not always identify a profile match. There is a way to extend that search and generate leads, called familial searching (FS). FS is used to identify close biological relatives of an unidentified DNA profile obtained as evidence. The basic premise is that DNA profiles of immediate family members, such as siblings, parents, or children, are likely to have more alleles in common than unrelated individuals. These familial profile matches can generate new investigative leads for law enforcement.

Currently, a few states are using FS under their state database laws, although none explicitly permit FS. Many agencies have yet to adopt policies related to FS, even though it has been found to be as effective as CODIS for identifying sources of evidence. The absence of clear ethical guidelines and policy regarding how to properly utilize FS prevents many local and state jurisdictions from adopting this investigational tool.

In order to address concerns and existing policies related to FS and to guide policy decisions by agencies implementing FS, the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) issued the report Familial DNA Searching: Current Approaches in January 2015. The goal of the report was to provide information to policy makers, law enforcement officials, forensic laboratory practitioners, and legal professionals about how FS is being applied within the criminal justice realm.

Answers to the following questions about FS were provided by Mr. Rockne Harmon, a retired former prosecutor and member of the team that produced the report for the National Institute of Justice.

What is familial DNA searching?

Familial searching (FS) is an additional search of a DNA profile in a law enforcement DNA database that is conducted after a routine search fails to identify any profile matches. The FS process attempts to provide investigative leads to agencies engaged in the pursuit of justice by identifying a close biological relative of the source of the unknown forensic profile obtained from crime scene evidence.

Continue reading “Familial DNA Searching for Criminal Forensics: Q&A”

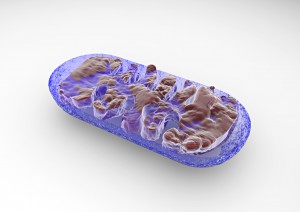

Scientists have known for some time that fetal DNA can be detected in the maternal bloodstream during pregnancy (1). Up to 10% of circulating cell-free-DNA (ccfDNA) can be attributed to the fetus. Fetal ccfDNA is released from the placenta, mainly through apoptosis, and enters the maternal bloodstream, where it can be easily collected and detected by PCR amplification. This method of collection has a much lower risk of miscarriage compared to more invasive collection methods such as

Scientists have known for some time that fetal DNA can be detected in the maternal bloodstream during pregnancy (1). Up to 10% of circulating cell-free-DNA (ccfDNA) can be attributed to the fetus. Fetal ccfDNA is released from the placenta, mainly through apoptosis, and enters the maternal bloodstream, where it can be easily collected and detected by PCR amplification. This method of collection has a much lower risk of miscarriage compared to more invasive collection methods such as