The tactic of “telling a good story” is nothing new within the business of selling, marketing and even educating about science. The word itself, “storytelling,” achieved buzzword status a few years ago in the corporate world, so it’s no surprise that it now touches industry scientists. But the importance of telling a good story within the realm of peer-reviewed scientific papers? That is something new, and it may impact how scientists write up their results from this point forward.

In a provocative scientific study published in PLOS ONE in December 2016, researchers from the University of Washington showed that “Narrative Style Influences Citation Frequency in Climate Change Science.” Perhaps the results they report are unique to climate change science—an area of science especially susceptible to public perception. But then again, perhaps not. This paper may be worth considering no matter what field of science you call your own.

The authors—Ann Hillier, Ryan Kelly, and Terrie Klinger—used metrics to test their hypothesis that a more narrative style of writing in climate change research papers is more likely to be influential, and they used citation frequency as their measure of influence. A sample of 732 abstracts culled from the climate change literature and published between 2009 and 2010 was analyzed for specific writing parameters. The authors concluded that writing in a more narrative style increases the uptake and influence of articles in this field of science and perhaps in scientific literature across the board.

Continue reading “Writing Scientific Papers: Is There More To This Story?”

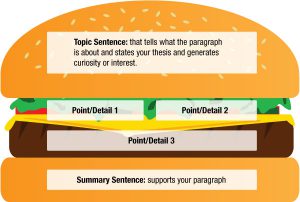

Parallel construction signals to the reader that two ideas are of equal importance. If two or more ideas or items are connected by a coordinating conjunction such as “and”, “but” or “or”, then those ideas should be expressed in parallel or equivalent grammatical constructs. Items and ideas of equal importance should be presented using equivalent grammatical structures. Items in a list should be parallel: all verbal phrases, all nouns, etc. Parallel construction guides your reader and helps your reader organize concepts on a first read of your text.

Parallel construction signals to the reader that two ideas are of equal importance. If two or more ideas or items are connected by a coordinating conjunction such as “and”, “but” or “or”, then those ideas should be expressed in parallel or equivalent grammatical constructs. Items and ideas of equal importance should be presented using equivalent grammatical structures. Items in a list should be parallel: all verbal phrases, all nouns, etc. Parallel construction guides your reader and helps your reader organize concepts on a first read of your text.

Good science writing is like good writing in any discipline, the writing communicates an idea or concept to the reader in a clear fashion. The goal of the science writer is not to sound smart or elitist by using vague verbs and abstract nouns that make the reader search for meaning in the text. Instead, the goal of the science writer is to explain scientific concepts and ideas clearly and engage the reader.

Good science writing is like good writing in any discipline, the writing communicates an idea or concept to the reader in a clear fashion. The goal of the science writer is not to sound smart or elitist by using vague verbs and abstract nouns that make the reader search for meaning in the text. Instead, the goal of the science writer is to explain scientific concepts and ideas clearly and engage the reader. Scientists are as likely to feel the smart of rejection as any other kind of writer. You slave over experiments trying to make sure that they have the proper controls to account for every possible artifact. You finally head to the computer keyboard and transcribe months, sometimes years, worth of labor into a few pages of text with some figures: your opus, which you send off on a wave of electrons to some distant editorial figure. And then you wait.

Scientists are as likely to feel the smart of rejection as any other kind of writer. You slave over experiments trying to make sure that they have the proper controls to account for every possible artifact. You finally head to the computer keyboard and transcribe months, sometimes years, worth of labor into a few pages of text with some figures: your opus, which you send off on a wave of electrons to some distant editorial figure. And then you wait.