In oncology, tissue biopsies are commonly fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin (FFPE). These FFPE samples can be used with immunohistochemical or molecular analysis for identifying biomarkers that guide the diagnosis and therapeutic management of patients. This fixation technique allows long-term storage of samples but impacts the integrity of nucleic acids. This makes extracting DNA and RNA from FFPE tissues in sufficient quantity and quality for molecular analysis techniques such as NGS analyses challenging for molecular oncology laboratories.

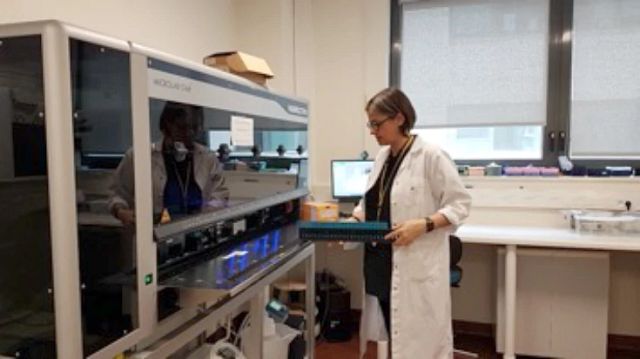

“At Rennes University Hospital, we receive many lung cancer samples with little material available, or samples of poor quality. The nucleic acid extraction step is therefore critical to get good yield. We have seen that it had a direct impact on the success of downstream analysis,” said Dr. Alexandra Lespagnol. Lespagnol is the Technical Manager of the Molecular Genetics of Cancer core lab at the University Hospital of Rennes in France.

In order to accommodate the increasing number of samples that needed to be analyzed, the Molecular Genetics of Cancer core lab of the University Hospital of Rennes initiated an automation project for extracting DNA from FFPE tissues. The lab also wanted to improve sample tracking and reproducibility of their results.

Continue reading “Improved FFPE Tissue Sample Processing with High-Throughput Automated DNA Extraction”