Sally Seraphin’s life in the research lab started with rats and roseate terns. Chimpanzees and rhesus macaques came next, then humans (and a brief foray into voles). When she pivoted to red-eyed tree frogs, Sally once again had to learn all kinds of new techniques. Suddenly, in addition to new sample prep and analysis techniques, she needed to get up to speed on amphibian care and husbandry. That led her to the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) in Woods Hole, MA.

“It’s a seaside resort atmosphere with experts in every technology you can imagine,” Sally says. “It’s a place to incubate and birth new approaches to answering questions.”

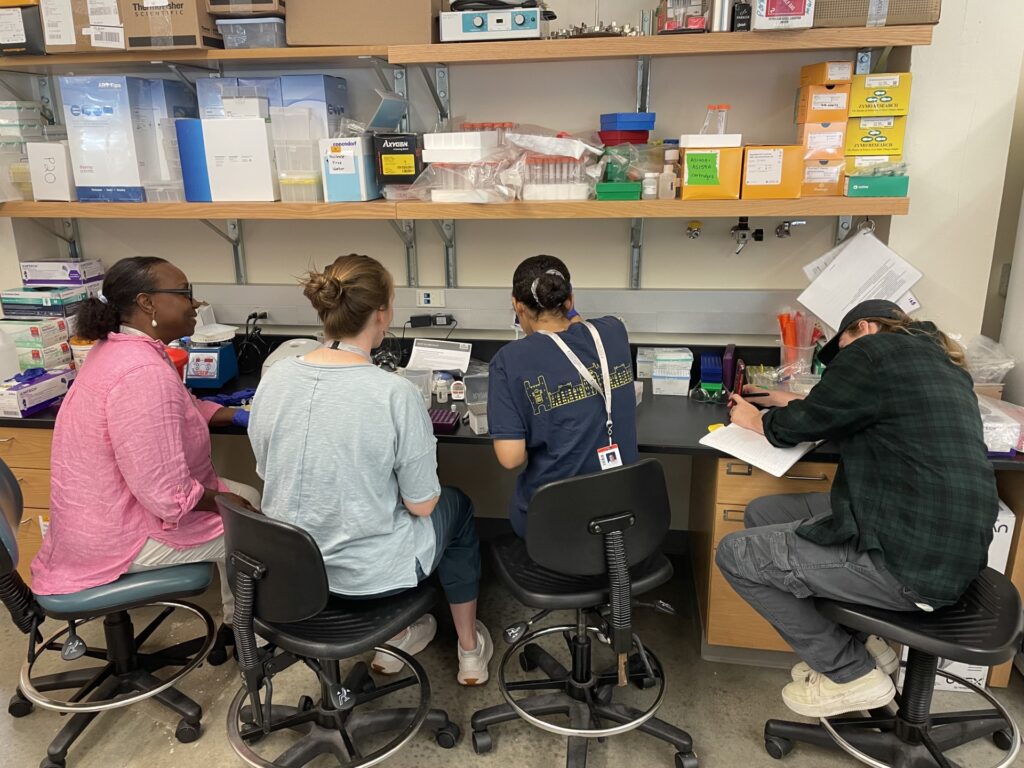

Sally spent the past two summers at MBL learning everything she needed to know about breeding and caring for amphibians. During that time, she also worked closely with Applications Scientists from Promega who helped her start extracting RNA from frog samples.

“The hands-on support from industry scientists is definitely unique to Promega and MBL,” she says. “It’s rare to have a specialist on hand who can help you learn, troubleshoot and optimize in such a finite amount of time.”

Adopting a New Model Organism

Sally studies how early stress impacts brain and behavior development. She hopes to deepen our understanding of how adverse childhood experiences connect to mental illness and bodily disease later in life. In the past, she studied how factors such as parental absence affected the neurotransmission of dopamine in primates. Recently, she changed her focus to developmental timing.

“Girls who are exposed to early trauma like sexual or physical abuse will sometimes reach puberty earlier than girls who aren’t,” Sally explains. “And I noticed that there are many species that will alter their developmental timing in response to predators or social and ecological threats.”

Continue reading “Raising Frogs Takes a Village: Accelerating Amphibian Research at the Marine Biological Laboratory”