![Bubonic plague victims in a mass grave in 18th century France. By S. Tzortzis [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/1b/Bubonic_plague_victims-mass_grave_in_Martigues%2C_France_1720-1721.jpg)

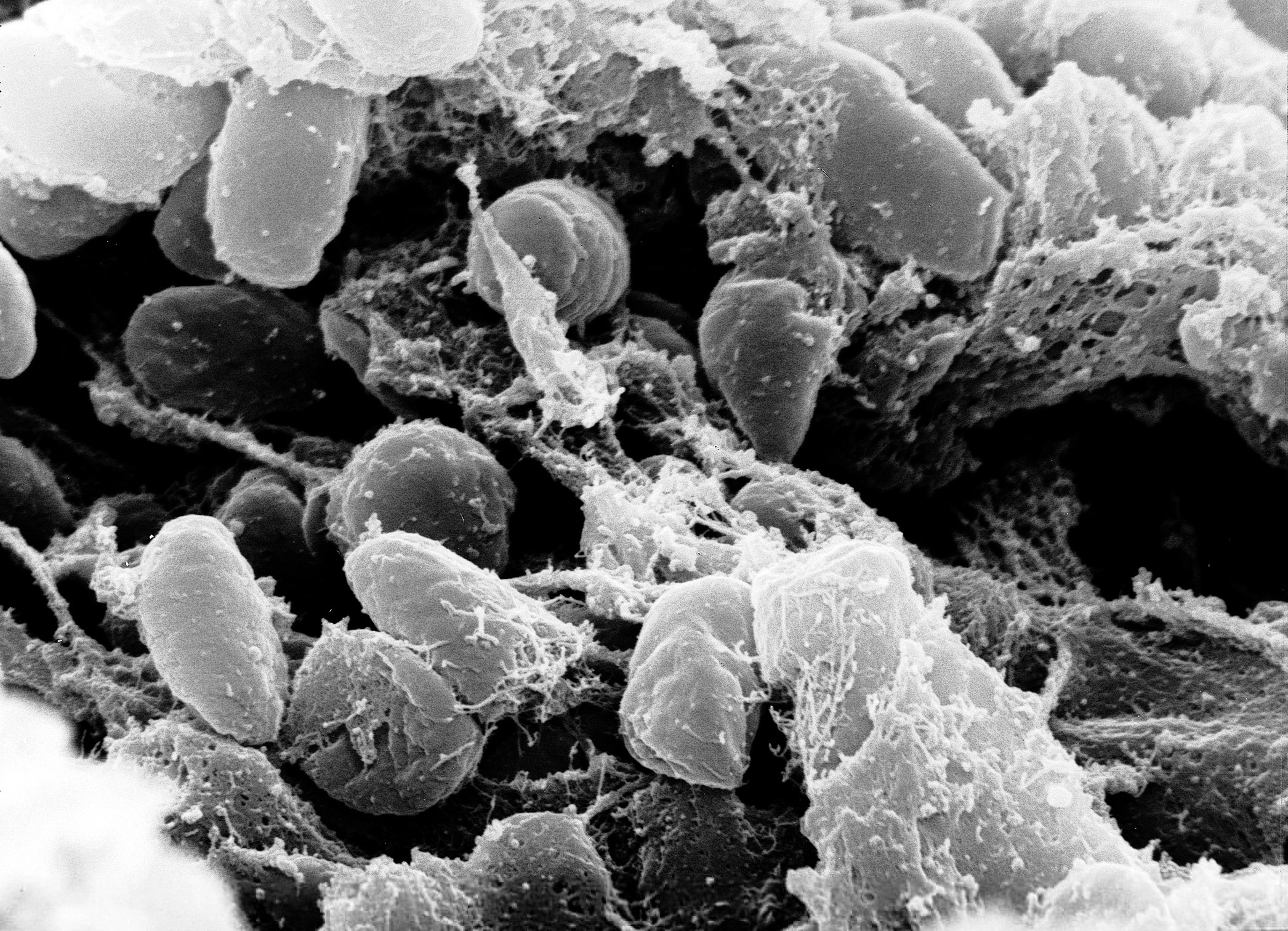

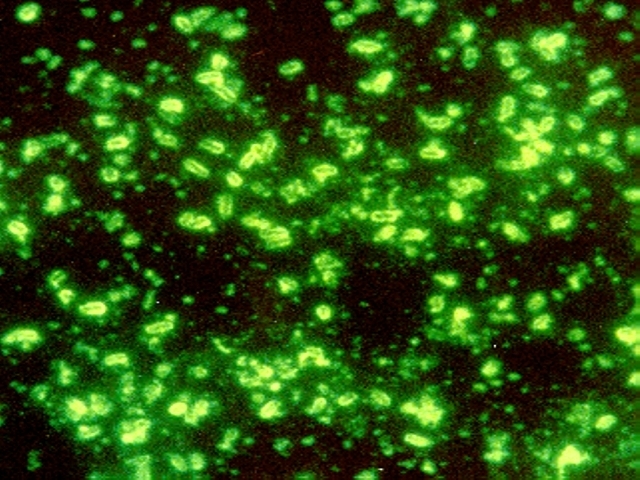

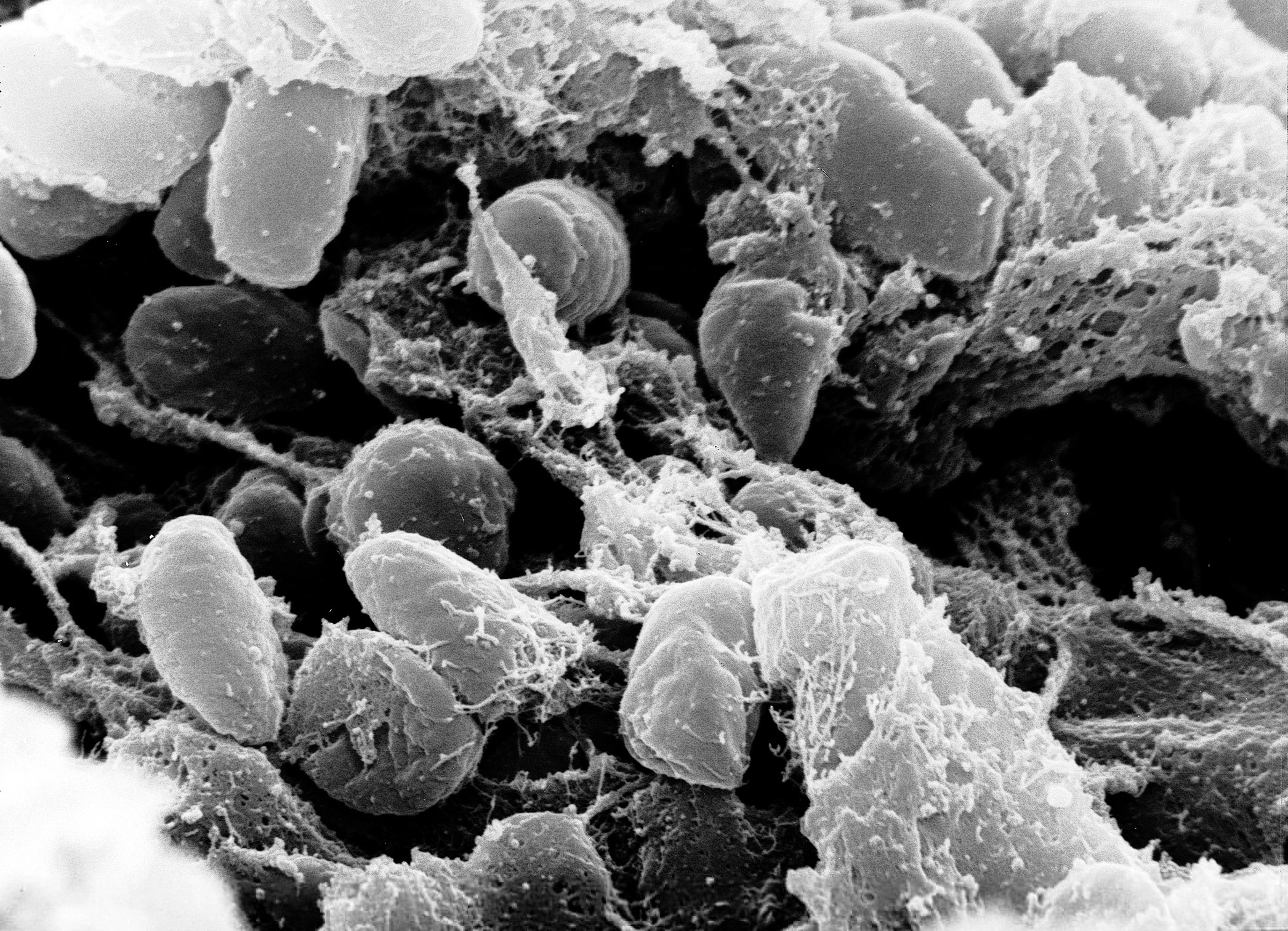

Teeth from 178 individuals in three different locations (two European, one Asian) were screened for Y. pestis infection using the plasminogen activator (pla) gene. Continue reading “Digging Up More Clues in the History of the Black Death”

![Bubonic plague victims in a mass grave in 18th century France. By S. Tzortzis [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/1b/Bubonic_plague_victims-mass_grave_in_Martigues%2C_France_1720-1721.jpg)

Teeth from 178 individuals in three different locations (two European, one Asian) were screened for Y. pestis infection using the plasminogen activator (pla) gene. Continue reading “Digging Up More Clues in the History of the Black Death”

Fridays are generally reserved for fun posts to share prior to the weekend. As we all know, fun is relative and to me, the latest news about how long Yersinia pestis has been entwined with human history is intriguing. I enjoy writing about the latest historical finding of Y. pestis even if I do earn a black reputation among my blogging colleagues (pun intended). Therefore, as soon as I saw the Cell article about Y. pestis found in Bronze age human teeth, I knew my blog topic was at hand.

Y. pestis has long been suspected in several plagues that occurred in the last two millennia. Publications in 2011 and 2013 used DNA extracted from teeth of human remains dated to the 14th century Black Death and 6th century Plague of Justinian to confirm Y. pestis was the causative agent in those devastating plagues. These results beg the question: How long has Y. pestis been infecting humans? The phylogenic trees generated from recent studies suggested Y. pestis has been with humans for as little as 2,600 years and as long as and 28,000 years. Equipped with these DNA-based tools, Rasmussen et al. asked if they could find evidence of Y. pestis in older human remains.

Continue reading “Yersinia pestis Reveals More Secrets From the Grave”

When I started writing about research on Yersinia pestis and the Black Death, I was amazed at the ability to recover 14th century bacterial DNA from human remains, show Y. pestis was the caustive agent of the Black Death and then sequence the strain to compare to modern Y. pestis strains. The publications I read always mentioned the three waves of pandemics that devastated human populations in the introduction, and the Black Death was not the oldest one. The putative first pandemic was the Plague of Justinian in the 6th century, named after the Byzantine emperor. Like with the Black Death, there is debate about whether Y. pestis is the causative agent of the Plague of Justinian. The research published in PLOS Pathogens built on earlier work to isolate and genotype the suspected Y. pestis causative agent from human remains in 6th century graves, but this time with more stringent protocols enacted to answer critics who questioned the authenticity of earlier results.

After writing my review of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA article “Targeted enrichment of ancient pathogens yielding the pPCP1 plasmid of Yersinia pestis from victims of the Black Death”, I vaguely wondered if the authors could have sequenced more than a single 10kb plasmid. If the single-copy chromosomal DNA was too scarce, maybe one of the other Yersina pestis plasmids that may exist at a higher copy number (e.g., pMT1) might be sequenced. Continue reading “Sequencing the Black Death is a Window to the Past”

Last year, I reviewed a PLoS Pathogens paper that found European Black Plague victims from the mid 14th century were infected with more than one clone of Yersinia pestis. While the Y. pestis-specific sequences amplified from several skeletal samples from various countries were evidence of the bacterium as the etiological agent, questions still remained about the virulence of the outbreak. What allowed that ancient strain of Y. pestis to cause such widespread death? Another group of researchers decided to further analyze the causative agent of the Black Plague by enriching for and sequencing one of the extrachromasomal plasmids present in the bacterial genome: the 9.6kb virulence-associated pPCP1 plasmid. Continue reading “Dance Macabre: Will 14th Century Remains Reveal the Pandemic Secrets of the Black Death?”

Last year, I reviewed a PLoS Pathogens paper that found European Black Plague victims from the mid 14th century were infected with more than one clone of Yersinia pestis. While the Y. pestis-specific sequences amplified from several skeletal samples from various countries were evidence of the bacterium as the etiological agent, questions still remained about the virulence of the outbreak. What allowed that ancient strain of Y. pestis to cause such widespread death? Another group of researchers decided to further analyze the causative agent of the Black Plague by enriching for and sequencing one of the extrachromasomal plasmids present in the bacterial genome: the 9.6kb virulence-associated pPCP1 plasmid. Continue reading “Dance Macabre: Will 14th Century Remains Reveal the Pandemic Secrets of the Black Death?”

I was confident I knew a few things about the bubonic plague: It was caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, which was transmitted to humans by fleas hitching a ride on the back of traveling rats. It spread rapidly and devastated populations around the globe, and because cats, a natural predator of scurrying rodents, had been killed, rats proliferated along with their deadly, infectious cargo. However, until I read a recent PLoS ONE article, I did not realize there was still debate about whether Yersinia pestis was the infectious agent for Black Death, the disease that ravaged 14th century Europe and killed one third of its population.