During the summer after my junior year of undergrad, I worked as a marketing intern for a health education nonprofit. I was a biology major, but by this time I knew I wanted to pursue a career in science writing, and this internship was my first real-world experience. It was an amazing summer, and by the time I walked into my exit interview, I was confident that my supervisor was pleased with my performance. However, she shared a piece of feedback that caught me off guard.

“I want you to speak up more,” she told me. “I know you have great ideas, but you’re always so quiet in our meetings brainstorming sessions.”

I wasn’t expecting to hear this, but as I reflected on my time with the organization, there were many times when I held back thoughts that I wanted to contribute. I believed that no one wanted to hear from the intern – that my voice was worth less than those of everyone else in the room. I was scared of speaking out of turn, or inserting myself into conversations above my level. I believed the problem would fix itself when I was in a permanent role and more comfortable with a team.

Unfortunately, three years later, one of my supervisors at Promega gave me almost identical feedback. This time I was even more shocked. I considered myself to be outspoken and actively worked to rein myself in when I worried about speaking over others. Still, there were certain situations when I knew I stayed quiet. As soon as a meeting started to get tense or difficult, I retreated into my proverbial shell. I was afraid of confrontation – of pushing back against a colleague’s ideas or backing up my own. My observant supervisor was able to pinpoint several specific moments when she knew I could’ve spoken up but chose not to.

According to Tom Kirkland and Lucy Kubly, the fear I was feeling in these meetings is common in the workplace. Tom and Lucy are longtime participants in the Promega Emotional and Social Intelligence (ESI) program. They recently teamed up to teach an ESI class titled “Transforming your Fear in Meetings” in which they discussed some of the reasons we might not get what we want out of a meeting. Using some of the fundamental tools of ESI, Tom and Lucy offer ideas for overcoming that fear and becoming a more present and active participant in these everyday situations.

Am I Good Enough: A Critical Look

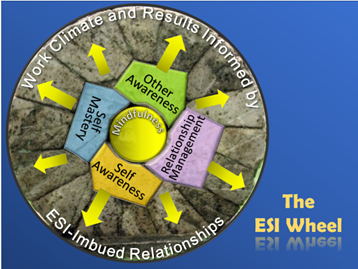

The ESI Wheel forms the foundation of Lucy and Tom’s class. Mindfulness forms the axle, which is surrounded by four important tools: Self-Awareness, Self-Mastery, Relationship Management and Other Awareness. (The ESI Wheel has been discussed in detail in other ESI blogs on Promega Connections.) In the course, Lucy focused on exercises that draw from self-awareness and self-mastery while Tom applied the other tools to examine how we form teams and relate to others.

Self-awareness is being more mindful about our immediate experiences. Check in with yourself – how are you feeling? To go deeper, what needs and emotions are you carrying that may influence how you perceive and react to reality?

Self-mastery requires acting on what we learn from our self-awareness. By applying our inner resources such as self-confidence and courage, we can intentionally regulate our experiences to align with our needs and goals.

In the ESI class, Lucy led an exercise that helped participants use their self-awareness to determine what they were really afraid of in a meeting. The two-phase exercise begins with the question “What are you afraid of?” Perhaps the answer is “I’m afraid of presenting to my boss about a timeline.” The partner would then ask, “What are you afraid of when presenting to your boss?” to which the answer might be “I’m afraid she will disapprove.” “What are you afraid of when she disapproves?” the conversation might continue, followed by “I’m afraid I might have to start from scratch.” The investigation of the fear continues until the fifth or sixth ask and a catastrophe response is initiated. This is when you know you have hit your core fear. It often involves severe loss of something or someone: “I’m afraid I will lose my job and be a failure to everyone I love.” We often operate and recognize the first or second level in our interactions at work. By performing this exercise, we can understand where our fear originates. It’s not something to change or make different, but the awareness helps us understand ourselves at a deeper level.

In the second phase, the goal is to investigate how likely it is is that the fear will occur. We have many worries and fears, but very few of them come true, and even those that do are often much better than expected. The partner now questions each fear one by one:

“Will she really disapprove?” they might begin.

“She will probably agree with about 80% of our suggestions.”

“Will you really need to start from scratch?”

“No, I will probably need to revise less than a quarter of the plan.”

Until eventually, the final level is reached:

“Will you really lose your job and be a failure to everyone you love?”

“No, one meeting will not be considered something to lose my job over, and even if I did lose my job, my family and friends care about me and will support me through hard times.”

Our surface-level concerns are almost always rooted in much deeper fears. The participants in Lucy’s class shared all kinds of worst-case fears: “Fear of abandonment,” “Fear of not being good enough,” “Fear of ending up alone,” and one that particularly resonated with me: “Fear that I’m a fraud.” However, by consciously considering and refuting our personal fears, we can use our self-mastery to shift from catastrophizing to rationalizing. I know that I’m not a fraud, but occasionally I need to remind myself of that.

None of these existential fears were likely to be true, especially within the context of a single meeting at work. As each step in the journey from the surface-level fear to the deeper insecurity is refuted, the meeting becomes less and less scary. Even if things don’t go perfectly, we can alter the stories we tell ourselves to recontextualize those situations in the bigger picture of our lives and careers.

What’s Really Going On Here?

To balance Lucy’s focus on the self, Tom led discussions on how we can better relate to the people around us. The “Other Awareness” segment of the ESI wheel encourages us to use mindfulness to extend compassion and empathy towards others. We must account for other people’s experiences and how they overlap with and differ from our own. All of this culminates with “Relationship Management,” which challenges us to use all of the other tools to effectively engage with those around us.

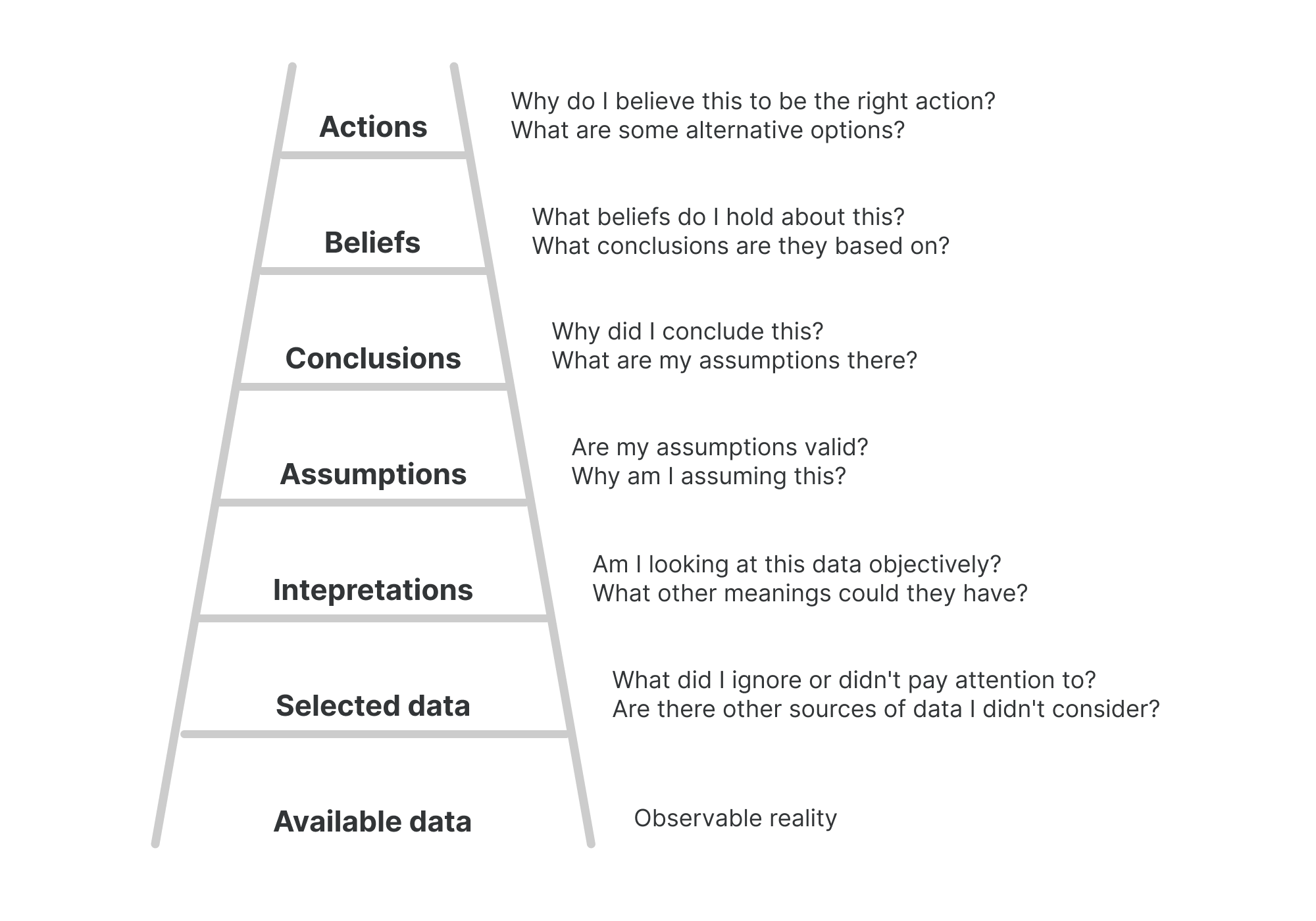

Tom uses a tool called the “Ladder of Inference.” This seven-step ladder helps us evaluate the reasoning upon which our decisions and conclusions are based. At the bottom of the ladder, we have our available data. This is the sum of all of the observations we can make about reality. However, as we move to the second rung, we can only take in so much data, so we select pieces based on our experiences and beliefs. Next, we prescribe meaning to that data, and begin to make assumptions. Our assumptions lead to conclusions, which then form beliefs. Finally, we take actions based on the beliefs we have formed about the situation.

We typically ascend the ladder in a split second. Something happens, and we respond. However, the different rungs can influence each other, leading to unsound judgments and conclusions that are far from reality. Our prior beliefs can influence the data we choose to consider. Incorrect assumptions lead to misguided actions. The Ladder of Inference gives us a framework to pause and consider whether each of our steps is supported by the one before.

First, identify where you’re currently standing on the ladder. Maybe you’re interpreting your selected pieces of reality, or maybe you’re ready to take action. Starting at that rung, work your way back down. Ask yourself what you’re thinking, and why you’re thinking that. Examine the dependencies as you go – how are your conclusions shaped by your assumptions? Why are you focusing on these specific pieces of data? Notice where your steps don’t line up, or where you might need to change your thinking.

When you reach the bottom, start working your way back up. As scientists, we love to rely on data. Examine all of your available data and choose the pieces that are most critical to assessing the situation. Interpret the data, craft reasonable assumptions. When you reach the top, you should be armed with a decision that is supported by rational thinking at each rung of the ladder.

In a meeting, we’re constantly running up and down the ladder. It’s easy to get wrapped up in a fast-paced discussion and let unhelpful thoughts shape our thinking. Maybe you’re making an untrue assumption about someone’s comment, or maybe you’re missing an important piece of data. Fear can alter our thinking and lead us to miss steps and take actions – including choices such as silence – that don’t help us meet our goals.

When you feel that fear, give yourself a moment to work through the ladder. Are you taking deliberate steps that are supported by the rungs below? Are you using empathy and compassion in your interpretations of others? Over time, you will learn which rungs tend to give you the most trouble and develop strategies to take extra care at those levels.

Conclusion

Fear can hinder our ability to communicate effectively, whether we’re staying silent or letting beliefs and assumptions alter our decision-making. Your voice matters, and your ideas should be shared! By working through our fear using the tools of ESI, we can connect more authentically with the people around us and build stronger, more productive teams.

The fear refute exercise is adapted from “The End of Stress: Four Steps to Rewire your Brain” by Don Joseph Goewey.

The Ladder of Inference was first introduced in “Overcoming Organizational Defenses: Facilitating Organizational Learning” by Chris Argyris. Learn more about the Ladder of Inference here.

Thomas Kirkland is a Sr Scientific Investigator at Promega Biosciences, Inc. in San Luis Obispo, CA.

Lucy Kubly is the Sr Manager of R&D Business Analysis and Administration at Promega Madison.

I met with both of them while planning this article, and it was one of my least scary meetings ever.

Thank you!