Have you ever had a day where you feel exceptionally good? As intake on the world kind of good? You feel so much better than the previous couple of days that you stop to wonder why.

Then it dawns on you.

The sun is out. It’s been cloudy for the past week but now—SUNSHINE.

You go out to lunch or for a walk just to take in those rays. Sure, it feels warmer than your darkened office space, but it’s the light rather than warmth that’s making a difference.

You purposely don’t wear sunglasses and it feels like the light is coming in through your eyes and massaging that part of your brain that is your happy zone. Are you imagining it or is the sun really affecting how you feel?

In a study reported in the September 2018 issue of Cell we learn that this is not a figment of your or my imagination (1). There is, in fact, a type of retinal cell that transports sunlight directly to the part of our brains that affects mood.

Eyes and the Body’s Master Clock

Circadian rhythms are innate time-keeping functions found in all multicellular organisms. This subject of the 2017 Nobel prize in Physiology or Medicine, circadian rhythms are fueled by daily light-dark cycles and are critical to the function of neurologic, immune, musculoskeletal and cardiac tissues (2). Nearly every mammalian cell is affected by circadian rhythms.

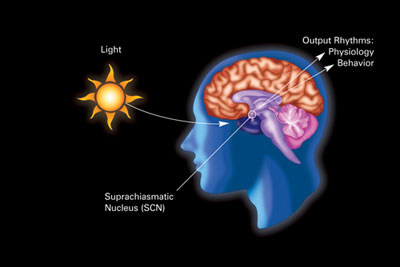

The human body has a circadian master clock, the suprachiasmatic nucleus or SCN. The SCN is a highly innervated tissue located in the hypothalamus (see image). It is connected directly to the retina by the optic nerve, and thus is influenced by external light and dark.

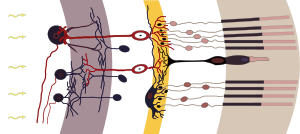

The retina of the eye is the light-gathering instrument for this organ. Historically, it’s been understood that the retina is composed of two cell types, rods and cones, that function in transmitting light and images to the optic nerve, which sends those signals to the brain.

Studies by Hattar et al. in the early 2000s identified another cell found in the retina, the melanopsin-containing intrinsically photoactive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs) as the transmitter of circadian light signals (3). Through this direct connection to the SCN, the circadian master clock, the ipRGCs can influence a wide range of light-dependent functions independent of image processing (4).

Now Fernandez et al. have identified multiple types of ipRGCs. They showed that ipRGCs that mediate the effects of light on learning work via the SCN, while the pathway for light influencing emotions is different.

They discovered a new target of ipRGC cells, the perihabenular nucleus (PHb). The PHb is a newly recognized thalamic region of the brain. The authors showed that the connection between light and mood is regulated by ipRGCs through the PHb versus the SCN. They show that the PHb is integrated into other mood-regulating centers of the thalamic region.

In Conclusion

Daylight, and lack thereof, does affect both our mood and our ability to learn. In this 2018 report, we have learned that the pathways for these effects are distinct, and gain an understanding of a new thalamic region by which the light and mood actions occur. This information could influence the development of better drugs and/or therapies for major depressive disorders.

For those of us with seasonal affective disorder, the evidence is undeniable—lack of light can cause issues, from sleep-wake problems, to mood and learning issues.

And while we can’t create sunshine, a special lamp or lightbox may help to gain some full-spectrum light. To learn more about how to choose such a lamp and when to use it, see this Mayo clinic article for details.

References

- Fernandez, D.C. et al. (2018) Light affects mood and learning through distinct retinal pathways. Cell 175, 71–84.

- Ledford, H. and Callaway, E. (2017) Circadian clock scoops Nobel prize. Nature 550, 18.

- Hattar, S. et al. (2002) Melanopsin-containing retinal ganglion cells: architecture, projections, and intrinsic photosensitivity. Science 295, 1065–70.

- Hattar, S. et al. (2003) Melanopsin and rod-cone photoreceptive systems account for all major accessory visual functions in mice. Nature 424(6944)76–81.

Anyone who has travelled across time zones knows how unpleasant it is when the regular rhythm of your biological clock is disrupted. Jetlag results when the body’s internal clock, or circadian rhythm is out of sync with external cues for “day and “night”, resulting in insomnia, extreme tiredness, difficulty concentrating and various other unpleasant symptoms.

Anyone who has travelled across time zones knows how unpleasant it is when the regular rhythm of your biological clock is disrupted. Jetlag results when the body’s internal clock, or circadian rhythm is out of sync with external cues for “day and “night”, resulting in insomnia, extreme tiredness, difficulty concentrating and various other unpleasant symptoms.