Several years ago, I made the move from academia to the biotech industry. Leaving my research in academia seemed like a huge risk to take, but it was a positive career change that I only recently realized was a long time in the making.

Before joining Promega, I was a post-doc at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. I worked on these fascinating enzymes that add nucleotides to the 3ʹ ends of RNAs, developed a Next-Gen Sequencing assay to measure their activities, discovered a bizarre and novel activity of one of the enzymes, and wrote a patent application.

I love science. Being immersed in a tough problem in the lab and then working as hard as I possibly can to solve it is so rewarding and satisfying to me! I really enjoyed my research project, but I found myself interested in a variety of other science topics. The thought of having my own lab where I worked on the same types of enzymes for 30+ years made me anxious. Why did I feel that way? I attributed it to the apprehension of the hard work it would take to establish a lab and get tenure.

Meanwhile, at UW–Madison, we had begun a campus-wide discussion to brainstorm about solutions for sustaining the biomedical research enterprise in the US. I attended almost every meeting and, overall, was left with an ominous feeling. Many scientists clearly loved their work but were frustrated and discouraged by the prospect of losing (or never getting) funding. Is this what I really wanted? I reminded myself of my enthusiasm for science and convinced myself it would be worth it once I had a lab up and running and was mentoring my own students.

I pushed my doubts aside and started applying for faculty positions. I was excited about the possibilities of new projects as I wrote my research proposal. But would these projects be good enough to get me interviews? I told myself that I wouldn’t know unless I tried. I did try, but didn’t end up going too far down that path.

While taking a break from writing, I saw a job posting at Promega: Scientific Instructional Designer. I had never heard of anything like that before, but the job description seemed interesting and unique. Designing training courses on Promega products sounded like a cool challenge! Maybe I should think about this… I considered my interest in a variety of science topics and had become OK with not knowing every minute detail about them. When I taught a senior undergraduate biochemistry course at UW–Madison, I really liked using interactive learning to help the students to apply basic concepts. Plus, the more I learned about the position, the more appealing it became. This sense continued during the interview process, and I was delighted to receive a job offer. It fits! I realized that this might be the change I needed to assuage my restlessness about moving forward with academia.

When I accepted the job, I was about a year into my role as a Chair of the 2016 Gordon Research Seminar (GRS) on Post-Transcriptional Gene Regulation, a meeting specifically for post-docs and grad students prior to the associated Gordon Research Conference. The time came for the conference, and I wondered about how I would be received as a GRS Chair who now works at a biotech company. Would they see me as a sell-out? Or that I didn’t truly appreciate research? To my surprise, I was not only welcomed, but congratulated for making the change.

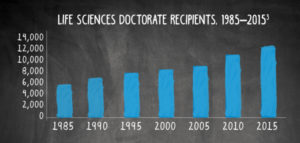

I had invited Jon Lorsch, Director of the National Institute for General Medical Sciences at NIH, to be the keynote speaker at the GRS and to discuss the role of early career scientists in the future of the biomedical research enterprise. Jon discussed modernization of graduate student education to emphasize developing skills to prepare young scientists for any job in science, not just academia. This change makes sense, as a 2012 NIH report found that only 20% of recent life sciences PhDs go on to become faculty members1. Between 2004 and 2011, the number of PhD scientists in the biomedical sciences field increased by about 38% (~26,000 in 2004 to ~36,000 in 2011) without a concomitant increase in faculty position openings2. Thus, a majority of recent PhD graduates needed to find jobs elsewhere. In fact, an analysis of the US Biomedical workforce revealed that four out of every five biomedical PhD scientists are employed outside of academia2. Despite this shift in career opportunities and outcomes, the model for graduate education has remained constant for decades, with the number of doctorate degrees awarded in the life sciences steadily increasing over time3.

As for my own career outcome, I realized that changing directions and shifting away from science academia didn’t mean that I stopped loving science. Moreover, I still utilize skills that I honed in grad school: versatility in learning new things, critical thinking to come up with creative ways to approach a problem, written and oral communication, working on teams, etc. The bottom line was that the opportunity at Promega was a better fit for me. Admittedly, it just took me a long time to accept that pursuing an academic science career wasn’t actually in line with what I wanted for my career and with what was truly important to me.

I’ll leave you with some advice that came out of the career panel held at the GRS (which consisted of scientists from industry, academia and government). This advice is widely applicable and hopefully will be beneficial to those planning their future career (or a career change!).

- Know yourself and your interests, and be true to them.

- Network and reach out to those in careers that you might be interested in.

- Recognize opportunities and seize them when they come to you.

- Set goals and make plans that allow you to achieve them.

- Do some research about your potential employers and what they are looking for.

References

- National Institutes of Health (2012) Biomedical Research Workforce Working Group Report (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). [Internet; Accessed January 6, 2019]

- Heggeness ML, Gunsalus KTW, Pacas J, et al. (2017) The new face of US science. Nature 541, 21–3 doi:10.1038/541021a

- National Science Foundation National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (NCSES) (2016) Doctorate Recipients from U.S. Universities: 2015 Data Tables (National Science Foundation, Arlington, VA).

Looking for a career in science? We have many options from research and development, to production, to quality assurance and more. See what opportunities await you at: https://bit.ly/3EEQqKF

Updated 4/9/2024 to correct broken links.