Following what feels like an exceptionally long and brutal winter, I for one couldn’t be happier about the arrival of Spring and the way it makes everything seem brighter and brand-new. Soaking in the soul-warming sunshine. Reveling in the sweet melody of chirping birds. Watching the earth literally coming alive again with greenery. And for those of us who love and are enthralled by scientific discoveries like myself, the report of a recent shiny new discovery in the world of cancer research is equally as day-brightening and spirit-lifting.

To suppress tumors or to not suppress tumors: that is the question.

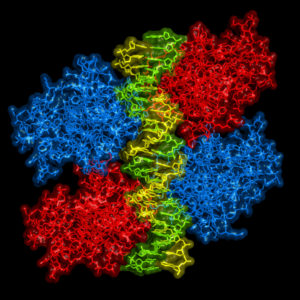

In the world of oncology, the protein known as p53 has long proven itself to be a primary target of interest. p53 operates as a tumor suppressor protein, often lauded as the “guardian of the human genome”, due to its dedication to governing controlled cell division and assessing damaged DNA. There are a number of cellular stressors that can wreak havoc on your DNA, including exposure to ultraviolet light or radiation, oxygen deficiency (hypoxia), and contact with hazardous chemicals.

Consider a normal-functioning p53 protein as the quality control person in a production factory. The p53 protein evaluates the products, DNA, coming down the line and determines an appropriate course of action for those that do not meet the quality standards.

Let’s say some less-than-quality DNA comes down the pipe. If the DNA is not too severely injured, p53 will alert and activate additional genes to repair the damage. However, if the products coming through are too marred to repair, p53 will shut down the whole factory, if you will, by signaling for the cell to self-destruct via apoptosis. In doing so, p53 effectively impedes tumor development by inhibiting the ability for flawed DNA to further divide.

So, it would seem like p53 has proven itself to be an undeniably upstanding citizen of the protein variety, right? The unfortunate truth of the matter is p53 balances delicately on a double-edged sword, establishing itself as the veritable Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde of the cellular world: usually unquestionably good, but sometimes unspeakably evil. Continue reading “When Good Proteins Go Bad”