I am reminded daily that we live in an age of wonders. To find out where somebody lives, I plug in their address into any one of a number of mapping web applications, and instantly see their neighborhood, detailed satellite views, driving directions, even gas stations nearby should I need to stop by one. I can similarly figure out who people are and how I’m connected to them with a variety of social networks, and all these data are delivered painlessly: No flipping through gargantuan phonebooks, no need for obscure incantations to formulate database queries.

Scientific visualization has been catching up in fits and starts to this new world of ubiquitous and trivially accessible relationship data. This is partly due to the inherent complexity of scientific data, and partly due to the vastly smaller user base that would benefit from such an endeavor, and the limited resources available to researchers. There are certain scientific datasets, however, that are eminently suited to benefit from this new visualization paradigm.

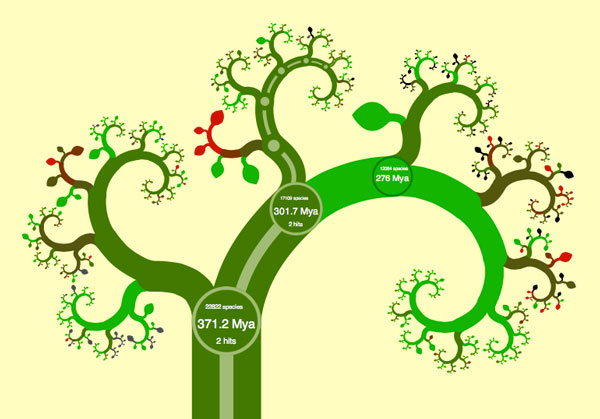

Consider the phylogenetic tree of living creatures: representing how different species are related to each other. Long ago in school, for example, I was taught that tetrapods (vertebrates, except for the fishes) were grouped into amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals, pretty much in that order and with very little sense of how little or much diversity each of those groups encompassed. Since then, genetic sampling has revolutionized our understanding of the tree of life. However I’m pretty confident that kids are still taught about amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals, in pretty much that order. Perhaps somebody mentions that the dividing lines aren’t quite as clear-cut anymore, but that probably just muddles things even more.

James Rosindell and Luke Harmon took on this problem of visualizing the modern, genetics-based understanding of phylogeny in a way that is accessible to the general public. Their approach was inspired by the navigation conventions of Google maps, and by the aesthetics of fractals, especially the tree-like L-systems. Continue reading “OneZoom, The Fractal Phylogenic Tree Explorer”