This guest blog post is written by Tian Yang, Associate Product Manager at Promega.

There are often challenges with translating results from a test tube into a living system, demanding more physiologically relevant assays. In drug discovery, demonstrating a compound’s ability to modulate its target protein in live cells is a critical step in the hit-to-lead workflow. A variety of cell-based assays can be used to assess a compound’s activity in live cells. Take kinase inhibitors as an example, these assays can range from substrate phosphorylation assays that more directly report on the activity of target kinases, to genetic reporter assays or cell viability assays that assess the downstream effects of target modulation.

In the case of Tivantinib, several pieces of data from its development were used to establish its role as an inhibitor of MET kinase. MET Kinase is a prominent target for anti-cancer therapeutics due to frequent MET dysregulation in a wide range of tumors. For example, over-activation of MET drives cancer proliferation and metastasis. In the initial report on Tivantinib, in addition to biochemical activity assays performed with purified MET, the activity of Tivantinib in cells was verified by several methods, including: 1) inhibition of phosphorylation of MET and downstream signaling pathways, 2) cytotoxicity in cancer cell lines expressing MET, and 3) antitumor activity in xenograft mouse models (1). Additionally, a co-crystal structure of the MET-Tivantinib complex was solved, seemingly confirming that Tivantinib is a bona fide MET inhibitor capable of engaging MET in live cells (2). Based on these observations and other pre-clinical data, Tivantinib appeared to be a promising drug candidate and was taken through phase 3 clinical trials targeting cancers with MET overexpression. However, Tivantinib ultimately was not approved as a new therapeutic, failing to show efficacy in these phase 3 clinical trials (3,4).

Within three years of the initial publication on Tivantinib, two separate articles challenged the mechanism of action in Tivantinib-induced cytotoxicity of tumor cells (5,6). Authors for both articles showed that Tivantinib can kill both MET-addicted and nonaddicted cells with similar potency. Both articles also concluded that perturbation of microtubule dynamics, instead of MET inhibition, is likely responsible for the cytotoxicity observed with Tivantinib. Considering the failed clinical trials and uncertainties regarding the mechanism of action, one may wonder if the original pre-clinical work adequately determined if Tivantinib effectively binds and inhibits MET in cells? If Tivantinib’s cellular engagement to MET was assessed directly rather than by MET phosphorylation analysis, would a different pre-clinical recommendation have been made?

Cellular Target Engagement and its Role in Probe Development and Drug Discovery

When developing a new small-molecule chemical probe or therapeutic agent, understanding how a compound interacts with its target is a critical step. Traditionally, the characterization of target-compound interaction is frequently done with biochemical assays, which are target-specific, quantitative, and often simple to perform. However, biochemical assays lack the complexity of the cellular environment, where factors such as membrane permeability, competition by endogenous ligands, and formation of protein complexes can impact compound binding. To assess the compound’s effect on the target in live cells, cellular functional assays can be used, which report on the compound’s downstream effects, including gene expression or cell viability. The interpretation of the results of the cellular functional assays can be more complicated, as off-target interactions, indirect mechanisms, and/or compensatory pathways can all influence the assay results. When the biochemical assays and the cellular functional assays do not agree, the discordance presents a significant challenge in chemical probe and drug development. A compound may show strong activity in a biochemical assay but fail to engage the target inside a cell due to factors such as poor permeability, presence of cellular metabolites, or protein interactions not represented in the biochemical format. Likewise, a compound that alters cellular function may do so through unintended pathways involving off-target proteins, rather than direct inhibition of the target of interest.

Cellular target engagement assays that directly measure binding of the compound to its target within live cells can bridge the gap between biochemical characterization and cellular function by providing direct evidence of the interaction. These cell-based assays should be target-specific, allowing researchers to confirm compound engagement to the target(s) of interest in a more biologically relevant context. Cellular target engagement assays can be used to optimize compounds for improved cellular potency, affinity, and permeability, as well as help validate the mechanism of action. Indeed, cellular target engagement is identified as a critical pillar for the process of cell-based, preclinical target validation in drug discovery (7).

Chemical probes are often used alongside complementary genetic techniques like siRNA, CRISPR, and genetic knockouts to validate a target’s role in healthy and disease models. While these two approaches often yield concordant results, discrepancies occasionally arise (8). Without direct confirmation of target engagement by the chemical probe, such discrepancies could be interpreted as a lack of specificity for the chemical probe. However, direct evidence of on-target engagement by the chemical probe can reveal that differences between pharmacological and genetic outcomes may stem from underlying biological distinctions. For instance, genetic methods generally remove both enzymatic and structural or scaffolding functions of a target, whereas chemical probes typically only inhibit the enzymatic function, leaving structural roles intact. Recognizing the biological nuances can lead to the exploration of alternative therapeutic strategies or novel modalities that leverage or preserve these distinct target functions.

Methods to Measure Cellular Target Engagement

While a variety of techniques are available for characterizing compound-target interactions in biochemical systems, measurement of target engagement in cells is more challenging. Nevertheless, several methods have been developed to measure compound binding to targets inside live cells, and the more common ones are described here (9).

Broadly, the cellular target engagement methods can be grouped into probe-free techniques and probe-dependent techniques. The probe-free techniques typically exploit the changes in protein stability upon ligand binding, and the Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) is a prominent example. In CETSA, cells are heated to different temperatures, and proteins that are stabilized by drug binding remain folded, while unbound proteins denature and aggregate. The unaggregated fraction can be detected using immunoassays, which recognize the target protein of interest, or via mass spectrometry.

Reporter-based CETSA assays are derivatives of the CETSA technique. By introducing a reporter tag fused to the target protein of interest, the aggregation of the target protein can be more easily detected via the appropriate reporter assay, thereby simplifying assay development and enabling higher throughput. Both CETSA and reporter-based CETSA can potentially be used in compound hit finding for targets lacking established ligands.

Probe-dependent techniques rely on an established ligand for the target of interest to develop a suitable probe. However, these techniques offer the advantages of directly measuring binding and target occupancy of a test compound and can be performed at physiological temperature. Chemical proteomics using mass spectrometry and an affinity- or activity-based probe has served as a powerful tool for probing proteome-wide binding interactions. The probes used in this method can be derived from compounds of interest or promiscuous tool compounds that broadly engage a group of related targets. A capture moiety is also incorporated into these probes, allowing for the isolation of probe-bound targets from the cellular milieu prior to detection by mass spectrometry. The engagement of unmodified test compounds is measured by the displacement of the probes from the targets, which leads to a reduction in target enrichment in the quantitative mass spectrometry analysis.

NanoBRET® Target Engagement (TE) method is another probe-displacement method utilizing bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) to characterize compound-target interactions in live cells. The NanoBRET® TE platform relies on energy transfer between a NanoLuc® luciferase tagged target (donor) and a fluorescently labeled small molecule tracer (acceptor) that binds the target. When the two are in close proximity, energy transfer occurs, producing a BRET signal. Displacement of the tracer by compound binding leads to a loss of BRET signal, allowing for the measurement of cellular target engagement. As the BRET signal can be detected in real-time from live cells, the NanoBRET® TE technique allows for both equilibrium affinity measurements and kinetic residence time analysis of compound engagement.

Schematics of commonly used techniques for assaying cellular target engagement.

Tivantinib Does Not Appear to Directly Engage MET in Cells

Returning to Tivantinib and the questions posed about its cellular target at the beginning of this blog, we have presented cellular target engagement assays as an alternative and a more direct approach for assessing Tivantinib’s binding to MET kinase. If Tivantinib was assayed with a cellular target engagement assay, would Tivantinib effectively bind MET? We attempted to answer this question by measuring Tivantinib engagement to MET using the NanoBRET® TE platform.

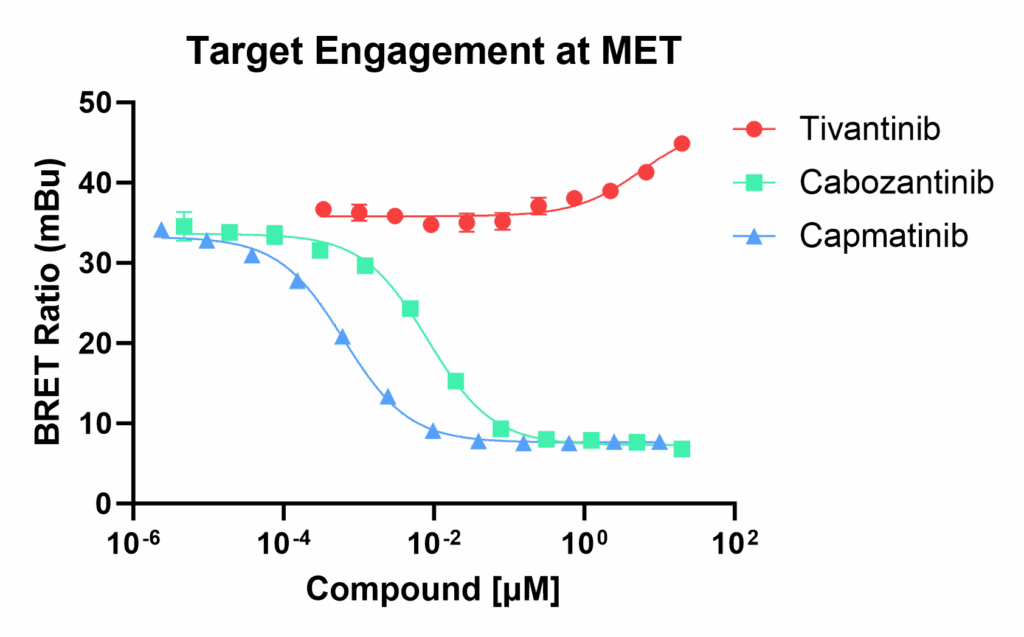

The NanoBRET® TE assay was used to quantify apparent cellular affinity of Tivantinib and two FDA-approved MET inhibitors (Cabozantinib and Capmatinib) for MET.

The NanoBRET® TE assay did not show meaningful engagement to MET kinase in live cells, which is contrary to the results from the phosphorylation assays in the original report of Tivantinib. However, using the cellular NanoBRET® TE MET assay with two FDA-approved kinase inhibitor drugs targeting MET, Cabozantinib and Capmatinib, resulted in nanomolar affinity for each inhibitor. This NanoBRET® TE assay result agrees with the reported chemical proteomics finding that a Tivantinib-based affinity probe displayed low enrichment of MET from cells, suggesting weak MET engagement by Tivantinib (10). Together with the studies identifying microtubules as the likely target for Tivantinib, the cellular target engagement assays provide convincing evidence that Tivantinib does not directly inhibit MET in cells.

Reviewing the original report of Tivantinib can provide clues to how this drug candidate may have been mischaracterized as a cellular MET inhibitor. It can be tempting to argue that a 24-hour drug treatment prior to the analysis of target phosphorylation provided an opportunity for off-target effects and/or compensatory pathways to confound the results, contributing to the mischaracterization of Tivantinib as a MET inhibitor. However, it can be challenging to know a priori the optimal conditions for measuring the drug’s effect in a cellular functional assay such that the on-target effect can be readily differentiated from other cellular processes. It is important to note that cellular functional assays that report a target’s activity further downstream of compound-target binding, such as cytotoxicity, are more susceptible to interference from several factors including non-specific interaction, off-target effects, and cross-talks from other cellular processes. Careful experimental design and data interpretation are needed to link compound treatment and biological response. Cellular target engagement assays provide a powerful tool to establish on target binding that links to the desired biological effect.

Conclusion

Cellular target engagement assays represent a crucial advancement in drug discovery and chemical probe development, bridging the gap between biochemical characterization and functional cellular responses. This gap is underscored by the case study of Tivantinib, where even rigorous biochemical and cellular functional assays can lead to misinterpretations of a compound’s mechanism of action. Targeting microtubules instead of MET would not immediately diminish the therapeutic potential of a drug such as Tivantinib, as microtubule-targeting agents have had clinical successes (11). The mischaracterization of the cellular target of Tivantinib had significant impact on the design of the clinical trials, which likely contributed in part to its failure at the clinical stage (5). Furthermore, the mischaracterization has persisted despite the publications showing the lack of MET engagement in cells, with recent publications still using Tivantinib to probe the role of MET in cancer (12, 13).

The Tivantinib example highlights the importance of incorporating cellular target engagement assays early in the drug discovery process to determine true compound-target interactions in cells and optimize for it. By directly assessing binding interactions in the physiologically relevant context of live cells, researchers can avoid costly mischaracterizations and late-stage failures by focusing efforts on compounds with validated mechanisms of action. As new technologies continue to expand the capabilities of cellular target engagement assays, they will facilitate the development of more reliable chemical probes and effective therapeutics, as well as guide the scientific community toward clearer, more accurate interpretations of biological data.

References:

- Munshi, N., et al. (2010) ARQ 197, a Novel and Selective Inhibitor of the Human c-Met Receptor Tyrosine Kinase with Antitumor Activity. Mol. Cancer Ther. 9(6), 1544-1553.

- Eathiraj, S., et al. (2011) Discovery of a Novel Mode of Protein Kinase Inhibition Characterized by the Mechanism of Inhibition of Human Mesenchymal-epithelial Transition Factor (c-Met) Protein Autophosphorylation by ARQ 197. J. Biol. Chem. 286(23), 20666-20676.

- Rimassa, L., et al. (2018) Tivantinib for second-line treatment of MET-high, advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (METIV-HCC): a final analysis of a phase 3, randomised, placebo-controlled study. Lancet Oncol. 19, 682-693.

- Kudo, M., et al. (2020) A randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 study of tivantinib in Japanese patients with MET‐high hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 111(10), 3759-3769.

- Basilico, C., et al. (2013) Tivantinib (ARQ197) Displays Cytotoxic Activity That Is Independent of Its Ability to Bind MET. Clin. Cancer Res. 19(9), 2381-2392.

- Katayama, R., et al. (2013) Cytotoxic Activity of Tivantinib (ARQ 197) Is Not Due Solely to c-MET Inhibition. Cancer Res. 73(10), 3087-3096.

- Bunnage, M.E., et al. (2013) Target validation using chemical probes. Nat. Chem. Biol. 9, 195-199.

- Weiss, W.A., et al. (2007) Recognizing and exploiting differences between RNAi and small-molecule inhibitors. Nat. Chem. Biol. 3, 739-744.

- Robers, M.B., et al. (2020) Quantifying Target Occupancy of Small Molecules Within Living Cells. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 89, 557-581.

- Remsing Rix, L.L., et al. (2014) GSK3 Alpha and Beta Are New Functionally Relevant Targets of Tivantinib in Lung Cancer Cells. ACS Chem. Biol. 9(2), 353-358.

- Mukhtar, E., et al. (2014) Targeting Microtubules by Natural Agents for Cancer Therapy. Mol. Cancer Ther. 13(2), 275-284.

- Chilamakuri, R. and Agarwal, S. (2024) Repurposing of c-MET Inhibitor Tivantinib Inhibits Pediatric Neuroblastoma Cellular Growth. Pharmaceuticals. 17(10), 1350.

- DeAzevedo, R., et al. (2024) Type I MET inhibitors cooperate with PD-1 blockade to promote rejection of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Immunother. Cancer. 12, e009690.

Latest posts by Promega (see all)

- Promega Fc Effector Assays: Measure Every Mechanism - November 26, 2025

- Residence Time: The Impact of Binding Kinetics on Compound-Target Interactions - November 19, 2025

- Bringing Industry-Relevant Lab Experience to Undergraduate Life Sciences Majors with MyGlo® - November 4, 2025

One thoughtful comment