Within the broader March-long observance of Women’s History Month, March 8th marks the annual International Women’s Day. It’s a day of both celebration and reflection, dedicated not only to honoring the accomplishments and contributions that women bring to the table, but also to critical analysis of the areas where gender inequality still persists.

Although we’ve made big strides in the last few decades, women are still significantly under-represented in many fields of science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM). Women make up nearly 50% of the US workforce, but less than 30% of that number are STEM workers, and with women comprising less than 30% of the world’s researchers.

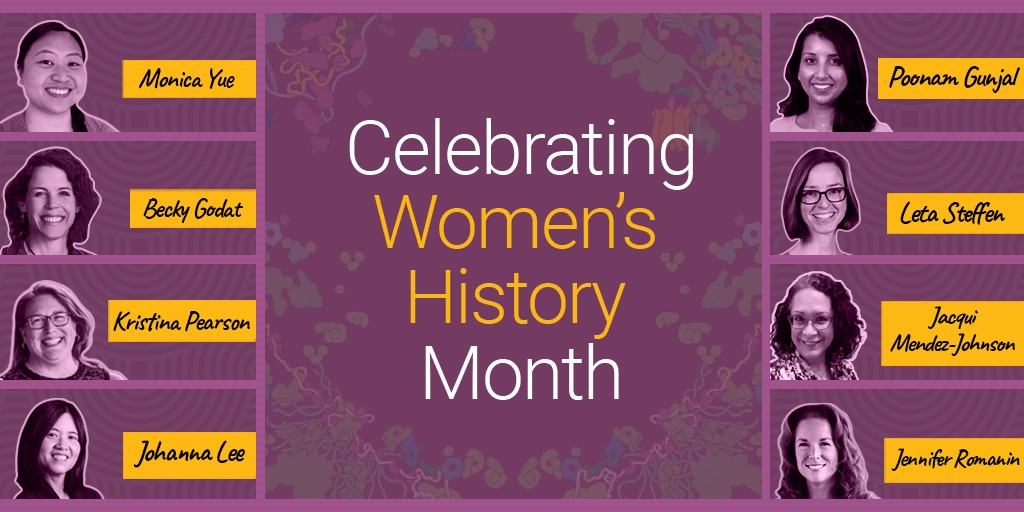

In honor of this year’s theme for International Women’s Day, Break the Bias, and as a woman in science myself, I was interested in exploring the challenges of anyone who identifies and lives as a woman in science, and the key factors that continue to perpetuate the gender gap in STEM fields. I invited eight of my female colleagues at Promega—diverse in roles, age, educational background, ethnicity, and experience—to sit down with me (virtually) to learn more about them and their experiences as women in STEM.

In no particular order, these women are: Johanna Lee, Content Lead, Marketing Services; Jacqui Mendez-Johnson, Quality Assurance Scientist; Kris Pearson, Director, Manufacturing & Custom Operations; Monica Yue, Technical Services Scientist; Jen Romanin, Sr. Director, IVD Operations and Global Support Services; Poonam Gunjal, Manager, Regional Sales; Becky Godat, Instrumentation Scientist; and Leta Steffen, Supervisor, Scientific Applications.

Though I feel like I could easily write an entire dissertation on what I have learned from these conversations alone, for the sake of brevity, I’ve split my learnings and takeaways into a series of three blogs. In part one, we’ll take a look at the key factors of gender stereotypes and male-dominated culture.

Why Does This Conversation Matter?

There are a lot of excellent, deeply-insightful and well-researched answers that could be share in response to the questions akin to “Why should I care?” and “Why do we keep talking about this?“. Here are few reasons why the topic of gender disparities in STEM warrant continuous discussion:

- Scientific research is more accurate and beneficial when gender is considered.

From studies on seatbelt safety to clinical trials for drugs, historically men have been treated as the default test subjects. But it’s important to recognize, as one study on whiplash so eloquently put it, “women are not scaled down men“. When studies neglect to factor in gender and sex as variables, it’s not uncommon to see a difference in safety and health outcomes between men and women play out in real world settings. - Women bring unique perspectives and experiences to research.

People from diverse backgrounds bring creativity to the way we approach problems, helping us see them from different angles and approach old problems in new ways. Including women and minorities in research allows these groups to be agents of change for their communities, by bringing to light their lived experiences, perspectives and the challenges they face. Recent studies also show that a group’s collective intelligence is strongly linked to the number of women in the group and the average levels of social sensitivity. Gender-diverse groups are able to work more collaboratively across a diverse set of tasks, which is crucial for research teams tackling the complex scientific issues we currently face. - We need more STEM professionals.

Since 1990, employment in STEM jobs has grown 79%, increasing from 9.7 million to 17.3 million, and between 2019 and 2029, STEM jobs are projected to grow 8.8%. It’s clear that we will continue to see increasing demand for STEM professionals, and that STEM fields are economic drivers that provide a wide range of career opportunities, and the number of female professionals will need to increase in order to help meet this demand. - Because we’re not there yet.

More attention has been directed at this topic in recent years, with various studies pinpointing many of the issues contributing to the STEM gender gap. While that’s certainly a step in the right direction, there is still work to be done. Continuing to examine the experiences and views of under-represented groups in STEM across multiple disciplines can help us gain insight, spread awareness, and develop effective strategies to successfully dismantle the systemic barriers that perpetuate the inequality gaps in STEM. Leveling the STEM playing field would be a stepping stone on the path to achieving a society with full gender equality.

Key Factor #1: Gender Stereotypes

When you think of the word “scientist”, who immediately comes to mind? How about when you hear the word “technology”? I would be willing to bet your first thoughts went to someone like Albert Einstein, not Emmy Noether; like James Watson and Francis Crick, not Rosalind Franklin; like Steve Jobs and Bill Gates, not Grace Hopper or Hedy Lamarr.

Although it’s not conscious or intentional, this is an example of implicit bias: your brain has naturally picked up on the pattern of seeing and hearing about more men in STEM, so when you think “STEM” you think “men”. We can have implicit biases towards a number of things—age, gender, race, religion, socioeconomic status—and it can be difficult for us to change these biases. However, some implicit biases that go unchecked or unchallenged can perpetuate harmful stereotypes that ultimately play a role in our social systems, contributing to problems like the systemic under-representation of women and other minorities in STEM.

“Women Aren’t As Brilliant As Men”

Throughout history, there was a pervasive misconception that women were intellectually inferior to men. And though we would like to think we have moved past such ridiculous and blatantly sexist generalizations, a recent study indicates that this implicit bias is still very much at play in this day and age. In the study, researchers asked over 3,600 men, women and children from over 78 countries if they agreed with the stereotype that men were more brilliant than women, which they said they didn’t. However, when these same people were given a test that measured their implicit bias, the results showed that between 60% and 75% of the participants showed implicit bias towards that stereotype.

The outcomes of this study builds upon a larger body of research illustrating that this stereotype of “male-brilliance” may contribute to the underrepresentation of women in career fields, like STEM, where success is perceived to depend on high levels of intellectual ability.

We see this stereotype play out early and often in education, with teachers and parents underestimating girls math abilities as early as preschool, though girls perform just as well as boys in math. Middle school girls pass algebra at higher rates than boys, and in science girls perform as well as boys and pursue advanced math and science courses at equal rates as they transition into high school. Researchers are not clear on the exact cause, but the gender gap begins to appear as girls enroll less and less in advanced STEM classes as they inch closer to college, and issues of race and class widens the STEM gender gap further. Even if we grow up feeling like we haven’t experienced gender bias or stereotypes actively working against us, we are unconsciously internalizing these biases. Jacqui voiced this exact issue based on her experience in overcoming her own internalized biases: “I think they were more in my head as a young person. We internalize all these things without knowing that we’re doing it. All these biases are getting imposed on us, and I just had to become comfortable with who I am. My color, my accent, not having a PhD—all of those things. I had to overcome my own complexes, inferiority complexes, right? I think that’s just so ingrained in our culture and how we grew up.”

“STEM Fields Are ‘Masculine’ or ‘Nerdy’ and Girls Aren’t Interested in STEM Topics”

Some additional common stereotypes in STEM perpetuate the idea that STEM-related activities are “masculine” or “nerdy”, and by default, girls just would not be interested in them.

One study evaluated if stereotyping STEM as a domain for “nerdy geniuses” would negatively relate to women’s STEM identity and if STEM identity would mediate the relation between stereotypes and STEM motivation. The results found that both gender and nerd-genius stereotypes contributed negatively to women’s STEM identity, and also found the STEM identity positively contributed to women’s STEM motivation, highlighting the impact different stereotypes have on women’s identification with STEM, which in turn impacts their motivation to pursue STEM paths.

In a similar vein, Kris shared with me that her high-school age daughter is interested in pursuing a career in science, and she told her about how important it is to study hard to best prepare herself for tackling challenging science course in college one day. As a result of her being an active participant and really engaged in her science classes, Kris’ daughter has heard comments from other girls calling her things like “smartypants” and “know-it-all”, words that fall into the same category as “nerdy”.

Luckily, studies show that parents, especially parents involved in STEM fields themselves, as well as teachers also carry influence in children’s decisions to pursue STEM, and can counterbalance these experiences for their kids by continuing to support and encourage their interests. Kris told me they’ve had several conversations in which she reminded her daughter to let comments like that slide off her shoulders, just like she and so many women in STEM professions, have had to do in the face of stereotypes and naysayers to keep pursuing this work that they really love.

In terms of girls not liking STEM stereotype, another study tested out gender stereotyping in computer science and found that telling girls that they don’t like STEM halves their resulting interest and involvement at any age. The researchers discovered that labelling activities in a stereotyped way ended up influencing children’s interest and willingness to participate, with 65% of girls choosing to join in activities they were told that both boys and girls like compared to only 35% of girls participating in the activities when they were told boys liked it better.

Based on these studies and examples, I think we can safely draw the logical conclusions that:

- Going forward, we all need to be mindful of the ways we may label or stereotype activities and identities to avoid negatively influencing children’s interests or discouraging their participation.

And… - Don’t tell women and girls what they should or should not like 😊

“Traditionally, Culturally and Historically, Women Are More Focused On Marriage and Motherhood”

For a good portion of history up to the not-so-distant past, the primary role and expectation in society for girls was that they grow up to be good wives and mothers. Access to education for women was few and far-between, and when it would finally become more available, there was usually a catch, in the form of no space to work, no funding, no recognition.

For many years (we are talking centuries) and in many cultures, access to education for women was conditionally dependent on the whether the stance of the era in question believed education to be a help or a hindrance to women’s roles as mothers and wives. For example, in ancient China, women’s education was limited to social roles and behaviors, in medieval Europe, women had to become nuns for any hope to receive more than a modicum of education, while some American women in the early 1800s argued that women required college-level education for the sake of being well-educated mothers.

Poonam told me that historically in India, that girls in general are considered burdens, largely because of the dowry system, meaning when a daughter eventually gets married the family will have to give dowry that they spend years saving up. She said that in terms of objectives for girls, they can go to school and they can have a career, but “the main objective of the parents of girls are to get them married off, because once they’re married off, then the responsibility is off of the parents’ heads. So, often the focus is more on making sure you know how to cook, making sure you know how to take care of a family, making sure you know how to build those relationships, so you’re always considered last.” She continued, “And I’m sure that’s in many cultures, it’s not just in the Indian culture, but I kind of grew up seeing my mom—seeing generationally—that you put yourself last and everything else first. So I don’t think that I was even able to sit down and say ‘Okay, what are my true passions? What are my true interests and what do I really wanna do?”

“I feel like that’s where we should be moving forward within the science community, just be supportive of whatever choices women make in their lives.”

– Johanna Lee

The Maternal Wall

One of the major patterns of gender bias is known as The Maternal Wall, which refers to the metaphorical wall professional women often find themselves running into after having children. In many cases, their competency and commitment to their work get called into question, prompting many of them to have to fight hard to prove themselves to be good scientists and good moms. All the colleagues I spoke with share that they experienced or witnessed this bias to some degree.

Before you even have kids, women are having to weigh options and make decisions regarding family planning. Monica doesn’t have children yet and told me about her experience in grad school of watching her postdoc navigate systemic challenges during her pregnancy. She said, “It was so difficult seeing her go through it because she had no support…she had no recourse for finding childcare very easily either and I just felt like—This is difficult. I don’t know if I’m ready to do this yet. So it just made me consciously think I need to push this back until I feel like I’m more stable. And there’s a lot of expectation for any woman who’s thinking ‘Should I start a family or not?’ and I saw it playing out as she was going through it.”

She went on to tell me that this postdoc was even considering going back to work only a week after giving birth, because she didn’t know if she could afford to be gone longer than that. “It made me pause and think more carefully about some of the important life decisions”, Monica said. “And I’m sure men consider this too, but I don’t know if they consider it quite as much.”

Johanna and I talked about the disadvantages women face as working parents, especially in STEM fields. “Think about all the long hours that people put into research and being in the lab all day and going in on weekends—it’s a lot of stress for anybody”, she said. “But because women kind of just take on the family burden, like even to this day, in modern times, we’re still taking more than half of the child-rearing responsibilities and family duties and that kind of thing. There’s a lot of reasons that lead to this, like it’s societal, it’s biological, but it’s kind of the reality. And I think it’s very challenging for women to continue on a research path because they’re taking on a lot more responsibilities than men. So even though there are a lot of outstanding women scientists, I feel like they have to work like 50% harder just to reach the level a lot of men do just because they may not have that burden on them.”

Studies support this, indicating that while the amount of time men spend parenting has increased over the last few decades from 2.5 hours per week in 1965 to 7 hours in 2011, women’s parenting time has also increased, from 10 hours a week in 1965 to 14 hours a week in 2011. Research also found, when factoring the time dedicated to child care in addition to time dedicated to working for pay and housework, the birth of a baby increased mothers’ total workload by 70%, which pans out to a total weekly workload increase of 12.5 hours for fathers and 21 hours for mothers.

Johanna continued, “What I think empowering women is, is really giving them a system or support from a very high level. If you want to have a child and also work full time, and be in the labs on weekends, we need to provide the right support system for those women.” Leta echoed this sentiment, agreeing that it would be great if structural support existed for both parents in our society, in order to alleviate some of the pressure of parental responsibilities that tend to fall by default on to mothers. She had both of her kids while working as a postdoc at Promega in R&D and although her supervisor was very supportive, she said, “..In this current society I think it’s even more difficult to be a working mom because there are only so many hours in the day, and if you’re a high-performing person, there are expectations you have for how much work you can generate and add value for your team, and it’s kind of at odds with feeling that same need to participate fully in your family life.”

Studies support this too, illustrating that mothers experience the greatest pressure trying to meet the unrealistic standards of the idealized role of motherhood. The pressure mothers feel to excel in all their roles can be compounded by additional unspoken expectations. For example, mothers in dual-earning families for shown to spend 10 more hours a week multitasking (doing unpaid activities like housework and childcare) than fathers, and are also more likely to take responsibility of the managing and organizing “worry work” tasks (e.g., making childcare arrangements, signing permission slips, scheduling appointments) than fathers.

Johanna drove home the point of what a no-win situation it can be to be a working mom, with any decision you make likely to draw criticism. When she was pregnant and made the decision to not continue with research, she heard things like, ”You’re wasting your PhD. Why are you not continuing on being productive?”. But when she later decided to go back to work, she said, “People would say things like, ‘Your child is still so young. Why are you going back to work full-time when you should be prioritizing your family? And I’m like, can you all just leave me alone, let me make my own choice, you know what I mean?”, and I believe generations of women, mothers or not, would understand down to their bones exactly what she means. “So I feel like that’s where we should be moving forward within the science community, just be supportive of whatever choices women make in their lives.”

Key Factor #2: Male-Dominated Culture

In the world of STEM, gender stereotypes and male-dominated culture currently coexist in a toxic symbiotic relationship, with the negative outcomes of one cycle reinforcing the negative outcomes of the other. For example, when we see fewer women pursuing degrees and careers in STEM due to gender stereotypes, the resulting absence of women can reinforce “proof” that women aren’t part of these fields because they aren’t for women. This, in turn, can bolster existing exclusionary, male-dominated attitudes and cultures in STEM which further effectively deter women and minorities from pursuing a degree or career in field in which they don’t feel welcome.

Exclusionary Environments

When we were discussing challenges that they have faced in their careers and educations, the experiences that both Leta and Jen shared illustrate this point perfectly. Leta shared that growing up, “I was in an accelerated math program and the class was largely boys, who liked to point out frequently that girls weren’t as good at math because ‘see how few girls are part of this program?“. And I had the same experience in physics in college, where I was one of few [girls]. I should say that most guys that I have worked with and most faculty that I’ve worked with, regardless of their gender, have been very supportive. But there is always a small and vocal portion that is not. So you do have to have some kind of personal fortitude if you want to keep going.”

In college, Jen had started off in electrical and computer engineering, with the initial desire to pursue biomedical engineering. When she was in the engineering program, she was very aware of her status as one of only four women in that program. Jen said, “When I went to talk to my 60-year-old male advisor, he literally said, ‘Well, if you can’t hack it…’ and it was like, wow. Okay, so you’re telling me you’re not gonna give me support here. Cool, good to know man. And I didn’t love [the material] enough to push through that lack of support that I was looking for.”

Prove-It-Again Bias

Another major pattern of bias observed regarding women in STEM is the Prove-It-Again bias, in which women have to prove themselves over and over again, constantly having their expertise called into question and successes disregarded. In this study, of the 60 female scientists interviewed and 557 female scientists surveyed, two-thirds of both those interviewed and those surveyed, reported that in order to prove themselves to their colleagues, they needed to provide evidence of their competence; black women were found disproportionately more likely to experience this type of bias compared to other women.

Environments like this, where women are presumed incompetent, and where women’s mistakes tend to be noticed more, and remembered longer than men’s, leads to this additional pressure on women in STEM, setting the expectation that they have to be perfect, always say yes, and never make mistakes.

This came up in my conversation with Becky as we talked about women’s societal expectations. She said, “I think the hardest part, and I think it’s going [away] with age, is always feeling like you have to be perfect. And I have a horrible time saying no to anybody or anything, and I don’t know if that’s part of that expectation, showing like ‘Yeah, I can handle one more thing, I can handle one more thing, and take on something additional’”, in reference to the many commitments she would take on as working parent, like being on the PTA and a variety of volunteer work.

When I asked if she thought if men feel similarly pressured, she replied, “No, because I think people listen to men more than women. So if you listen in on a meeting, it’s usually more dominated by men. And then sometimes you feel like when you have input, it’s small—and that can be in any conversation, right? How do you be confident in yourself and say ‘This is really what I believe and I deserve to be heard’.

A couple of studies illustrate men’s penchant for dominating meetings and conversations well: one study that recorded seven university faculty meetings, researchers found that the men in the meetings spoke more often, with one exception, and spoke longer, without exception. It was also determined that the longest comment made by a woman in all seven gatherings was still shorter than the shortest comment made by a man. A meta-analysis of 43 studies additionally revealed that men were more likely than women to talk over others, particularly in an obstructive way that allow them to assert dominance.

A Pleasant Contradiction

Contrary to all the biases and stereotypes we’ve looked at here, working at Promega does appear to be a bit of an anomaly in it’s treatment of women, at least when it comes to my own experience and the cross section of experiences shared by my colleagues. In all of these conversations, everyone shared at one point that they’ve never been on the receiving end of gender bias or discrimination while at Promega, they only experienced these instances in college or in their youth. Kris and Jen both shared with me that the only time they have ever really felt a noticeable difference in being a woman at work is in interactions with other companies, where a lot of the time there will be a lot more men at the table compared to our company.

Seeing women in a variety of roles at this company, including positions of senior leadership, sets a more inclusive tone and provides a welcome contrast to the biases and stereotypes many of us have experienced in our scientific educations and careers. It’s an encouraging demonstration that not only is there room for women in STEM, there’s room for them to grow and excel.

How Can We Address These Factors?

- Awareness — Recognizing inequality is the first step towards changing it. Engage kids early and promote awareness that girls are just as capable as boys.

- Support and Inclusion — Parents and teachers can work to provide equitable educational opportunities and encouragement for their daughters and female students. Support them with positive messages about their abilities. Seek out inclusive environments in schools, communities, and workplaces, and surround yourself with people and colleagues that value the voices and contributions of women and girls.

- Take Stock of Your Implicit Biases — Instead of perpetuating myths about why STEM isn’t for women, think about if that’s something you truly believe and where you think that stems from. Start paying attention to your thought patterns, challenge thoughts you think may be rooted in bias, and hold yourself accountable for re-evaluating and changing those patterns

Stay tuned for Part 2 of this series, out next week!

References

- American Association of University Women. The STEM Gap: Women and Girls in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics. Accessed February 2022.

- Arabia, J. (2021) Women in STEM Statistics to Inspire Future Leaders. Accessed February 2022.

- Bert, A. (2018) 3 reasons gender diversity is crucial to science. Elsevier Connect.

- Berwick, C. (2019) Keeping Girls in STEM: 3 Barriers, 3 Solutions. Accessed February 2022.

- Grant, A. (2021) Who won’t shut up in meetings? Men say it’s women. It’s not. The Washington Post. Accessed February 2022.

- Hammond, A. and Rubiano-Matulevich, E. (2020) Myths and Misperceptions: Reframing the narrative around women and girls in STEM. Accessed February 2022.

- Kricorian, K. et al. (2020) Factors influencing participation of underrepresented students in STEM fields: matched mentors and mindsets. International Journal of STEM Education. 7, 16.

- Riedl, C. et al. (2021) Quantifying collective intelligence in human groups. PNAS. 118, 21.

- Schoppe-Sullivan, S. (2017) Dads are more involved in parenting, yes, but moms still put in more work. Accessed February 2022.

- Storage, D. et al. (2012) Adults and children implicitly associate brilliance with men more than women. J Exp Soc Psychol.

- Tannen, D. (2017) The Truth About How Much Women Talk—and Whether Men Listen. TIME. Accessed February 2022.

- Thorpe, JR. (2017) Here’s How Women Fought For the Right To Be Educated. Bustle. Accessed February 2022.

- Timeline of Legal History of Women in the United States. (2021) National Women’s History Alliance. Accessed February 2022.

- Williams, J.C. (2015) The 5 Biases Pushing Women Out of STEM. Harvard Business Review.

- Williams, J.C., Phillips, K.W. and Hall, E.V. (2014) Double Jeopardy? Gender Bias Against Women of Color in Science.

- Wooley, A. and Malone, T. (2011) What Makes a Team Smarter? More Women. Harvard Business Review. Accessed February 2022.

- Yurcaba, J. (2020) Implicit Bias Study Reveals 75% of People Perceive Men to Be Smarter Than Women. Accessed February 2022.

One thoughtful comment