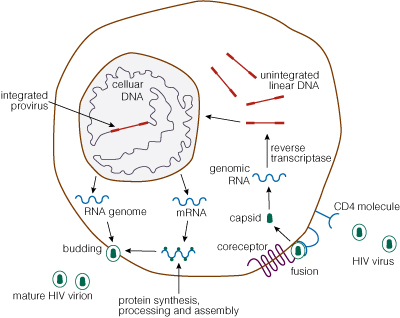

Recombinant adeno-associated viral (AAV) vectors are an appealing delivery strategy for in vivo gene therapy but face a formidable challenge: avoiding detection by an ever-watchful immune system (1,2). Efforts to compensate for the immune response to these virus particles have included immunosuppressive drugs and engineering the AAV vector to be especially potent to minimize its effective dosage. These methods, however, come with their own challenges and do not directly solve for the propensity of AAV vectors to induce immune responses.

A recent study introduced a new approach to reduce the inherent immunogenicity of AAV vectors (2). Researchers strategically swapped out amino acids in the AAV capsid to remove the specific sequences recognized by T-cells that elicit the most pronounced immune response. As a result, they significantly reduced T-cell mediated immunogenicity and toxicity of the AAV vector without compromising its performance.

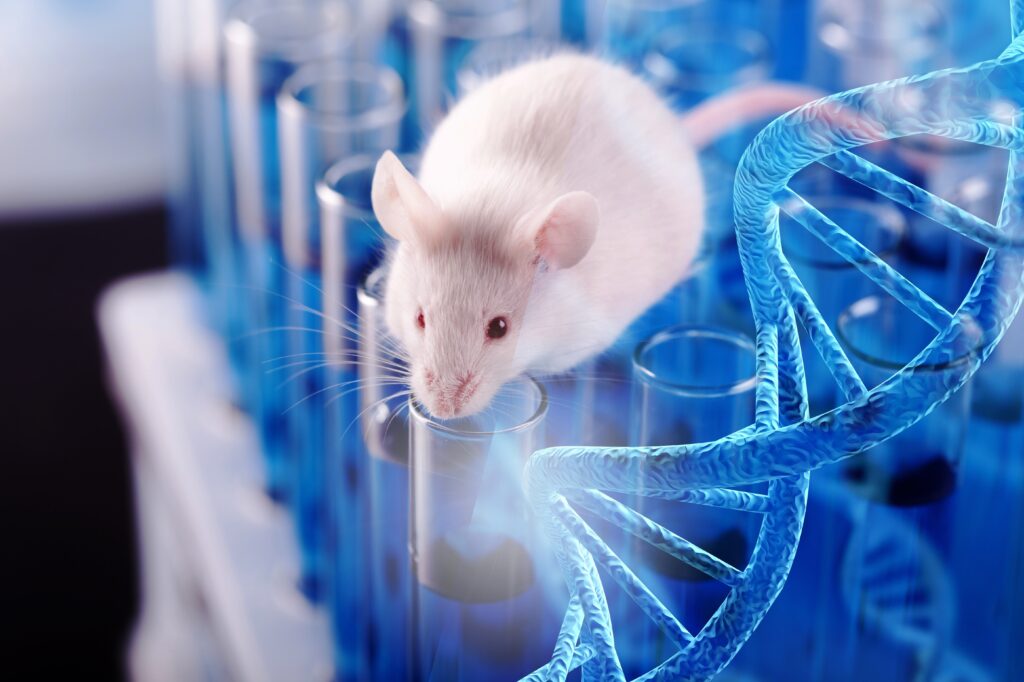

Read on to get more of the study details, which include the use of NanoLuc® luciferase and Nano-Glo® Fluorofurimazine In Vivo Substrate for in vivo bioluminescent imaging of the AAV variants’ distribution and transduction efficiency in mice.