Insects are a keystone species in the animal kingdom, often providing invaluable benefits to terrestrial ecosystems and useful services to mankind. While many of them are seen as pests (think mosquitos), others are important for pollination, waste management, and even scientific research.

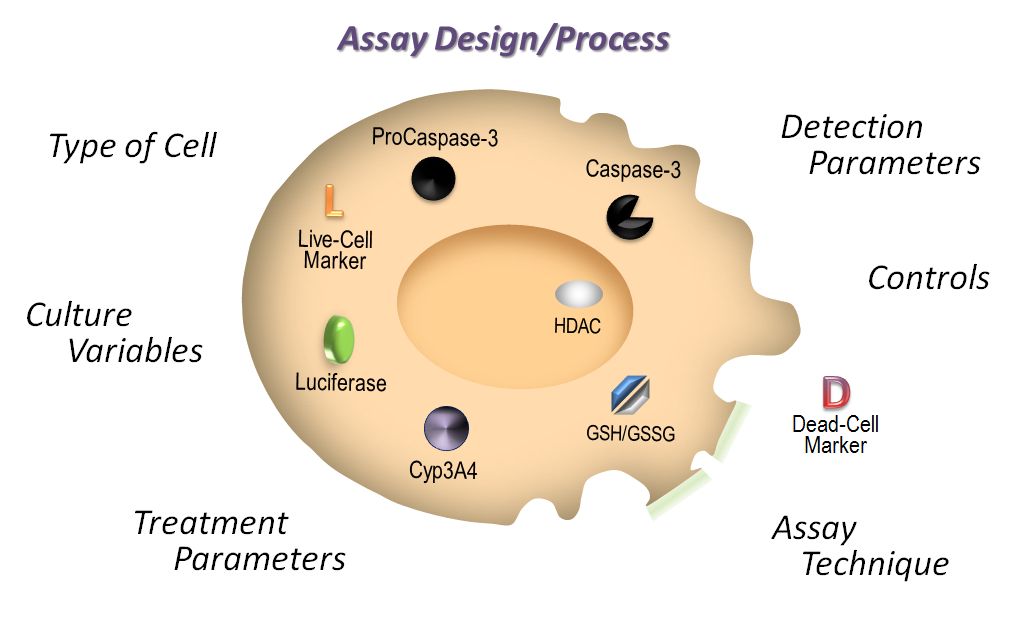

Insect biotechnology, or the use of insect-derived molecules and cells to develop products, is applied in a diverse set of scientific fields including agricultural, industrial, and medical biotechnology. Insect cells have been central to many scientific advances, being utilized in recombinant protein, baculovirus, and vaccine and viral pesticide production, among other applications (5).

Therefore, as the use of insect cells becomes more widespread, understanding how they are produced, their research applications, and the scientific products that can be used with them is crucial to fostering further scientific advancements.

Primary Cell Cultures and Cell Lines

In general, experimentation with individual cells, rather than full animal models, is advantageous due to improved reproducibility, decreased space requirements, less ethical concerns, and a reduction in expense. This makes primary cell cultures and cell lines essential contributors to basic scientific research.

Continue reading “Insects and Science: Optimizing Work with Sf9 Insect Cells”