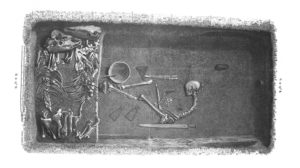

The elk tooth is small and ancient, with a crude hole bored through the top. It was likely worn as a pendant, but worn by whom? Was the owner male or female? Where did they come from? Did the pendant indicate their social status, mark a significant accomplishment, was it a gift, or was it worn as an expression of individuality?

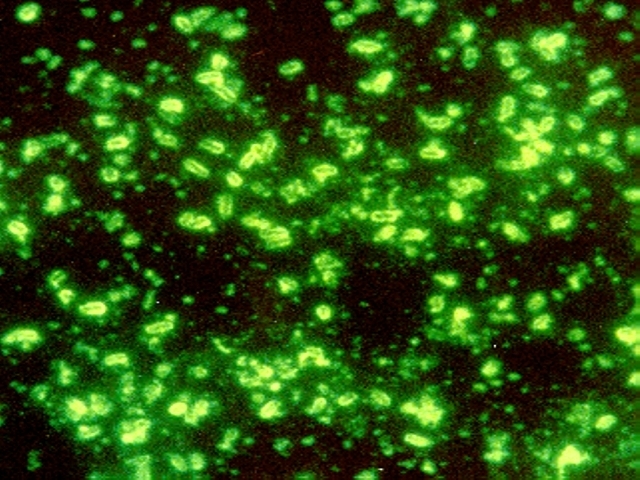

Artifacts such as personal ornaments and tools play a pivotal role in helping us understand the migration, behavior and cultures of ancient peoples. To date, this information has stopped short of providing insight into things like the biological sex or genetic ancestry of the individuals who may have worn or used these items, and thus limited our ability to accurately characterize societal roles and behaviors. Recent advances in DNA techniques and technologies, and one little pendant, might be changing that.